By Arvin Donley

June 2021

The Past, Present, and Future

of Milling

Innovation continues to drive one of the world’s oldest industries

©photocrew – stock.adobe.com

It’s been said the first flour miller was the first person who chewed on a wheat kernel. While the details of that milestone will never be known, we do know the transition to using millstones instead of molars to extract flour occurred around 6000 BC, and it remained the primary flour-making method for many centuries. Then, in 1779, at the beginning of the industrial era, the first steam mill was erected in London, England. A century later, the first mechanical roller mill was developed in Europe using stone disks. Since then, steel rolls have replaced stone rolls, pneumatic conveyors have replaced mechanical conveyors, automatic bagging machines have replaced human baggers and a whole host of state-of-the-art technology has been developed for the milling industry.

The milling process itself hasn’t changed much over the last century. Occasionally an innovation is introduced, such as color sorting technology to remove foreign particles and damaged kernels from the mill flow, but for the most part the advances have been upgrades of equipment already used in the process.

“Nothing overtakes the milling industry in great shockwaves,” said Jeff Gwirtz, a milling consultant and president of JAG Services, Inc., who for many years taught milling science at Kansas State University. “The group as a whole doesn’t just one day flip a switch and all of a sudden everyone is doing something new.

It’s a slower evolution. For someone who doesn’t understand the milling industry or someone who is fairly new, I tell them you have to understand that in the milling industry the jury’s still out on leather belting or the electric motor. I’m being facetious, of course, but usually the milling industry isn’t the first to jump at new technology.”

When new technology is introduced, it will most likely get a test run in a European mill. For one thing, the industry’s largest equipment suppliers are based in Europe, but also the millers in that region are more apt to embrace new technology than in other parts of the world.

Troy Anderson, vice president of operations for Denver, Colorado, US-based Ardent Mills Inc., the largest milling company in the United States, described the North American milling industry as being “fast followers” when it came to adopting the latest technology.

“I think the industry in North America is somewhat reluctant to be that initial test lab,” Anderson said. “It’s really hard to drive innovation through an industry that’s thousands of years old. The industry is often reluctant to make those major step changes.”

However, it would be inaccurate to say there haven’t been significant technological advances in the global milling industry over the last 100 years. The sheer amount of automation introduced to the industry in the last 30 years has improved mill performance in every way imaginable.

“Thanks to its development, the milling world has changed completely as it has allowed manpower to be rationalized through a whole series of ‘aids’ that it is able to offer, resulting in less human error, for example,” said Marco Galli, technological manager at Cremona, Italy-based Ocrim, a milling equipment manufacturer. “This has led to greater productivity thanks to a more rational management of the production cycles, all increasingly based on the correct management of data and information. I personally believe in that aspect the best is yet to come.”

When reflecting on the last 100 years of flour milling, one could point to dozens of innovations that led to a safer, more efficient milling process. Among those was the adoption of pneumatic conveying in the mid-20th century to move product through the mill. The advantages included fewer product leakages, product recovery and re-entry into the production cycle, no product or environment contamination, and far less maintenance than is required with mechanical conveyors. Another important innovation from the 20th century was the double high roller mill, which provides two grinding passages without any intermediate sifting. Many flour mills introduced double high roller mills to reduce capital costs. With this milling concept there is less installation, energy and maintenance cost, with fewer sifters, pneumatic lifts, filters, number of roll stands, spouting and auxiliary components and less space requirements. More recently, color sorters have become a game-changing piece of equipment in the wheat cleaning section of flour mills. Color sorters are used to remove ergot wheat, black tip, fusarium, burnt, other discolored grains and other inner contaminants.

“If I had to put my finger on one of the more recent innovative solutions, it would be the color sorting technology that’s grown in the industry, especially over the last 5 or 10 years,” Anderson said. “It’s become widely adopted and helped from an energy conservation and effectiveness standpoint of doing what we need to do in the plant.”

Perhaps the most significant development has been the utilization of computer-based automation that in recent decades has aided millers in countless ways. One of the early examples of this was the first lights-out flour mill going online in the 1980s, and although it hasn’t become the industry standard to operate unmanned mills remotely, the option is available in many plants.

Much of the industry’s technical innovation, particularly in the past 30 years, has focused on improving mill performance in three areas: Product and employee safety, energy savings and increased milling efficiency.

Product and employee safety

bar regarding food safety standards, milling equipment manufacturers have responded by designing equipment that addresses this issue.

“Food safety has had a major impact on the design of modern cleaning houses,” said Stefan Birrer, head of milling solutions at Uzwil, Switzerland-based Buhler AG. “With efficient color sorting, the precision of sorting has increased a lot. This has not only increased food safety but has contributed greatly to saving energy and raw material in our plants.”

Anderson said ensuring a safe food product, whether it is flour or a byproduct derived from the milling process, has become the top priority for millers.

“When I started in the industry 30 years ago, we didn’t want rocks, metals or anything harmful in the flour and we did everything we could at that time with the technology we had to make safe flour,” he said. “There were audits but there wasn’t a day-to-day conversation about it, whereas today it is the first point of every conversation. We have to make sure our product is safe at every one of our mills for every customer.”

Virtually every piece of milling equipment has been redesigned in recent decades with safety in mind. Sieves, for example, no longer use wood frames that can splinter or backwire or staples that can fall into the mill stream. Wooden spouting has been replaced with more sanitary stainless-steel spouting. Equipment such as roller mills, sifters, and purifiers have been designed to eliminate harborages for dust, dirt and insects.

“Years ago, when we taught the IAOM milling short courses at Shellenberger Hall (at Kansas State), I used to take people over by an old purifier and bang on it and watch the dead insects fall out of it,” Gwirtz said. “That had to do with design issues. They still have to have a place for the air to flow but they no longer have big cavities where the dust and dirt can accumulate along with insects.”

Not only are the flour products safer for consumers, but the mills themselves are less dangerous places to work as milling equipment manufacturers have made great strides in developing operator-friendly machinery that requires less maintenance and is enclosed so moving parts aren’t exposed.

“Today, the fact that the operator has less direct contact with the machines is a benefit in itself in terms of safety,” Galli said. “But this is not enough if the machines are not designed with this aspect in mind. In fact, the logic is not that of the operator going to the machine to check its condition, but it is the machine that ‘calls’ the operator when necessary. This is possible through the ongoing exchange of information between the machine and management system.”

Energy savings

Flour milling is a business with a notoriously tight profit margin, so milling companies are always looking to reduce costs. One of the biggest expenses for a milling operation is energy consumption since the process involves so many pieces of equipment. In recent years, great strides have been made by equipment manufacturers in developing energy-efficient machinery.

“The application of energy-saving technology, whether it’s variable frequency drive compressors or pneumatic systems that run just to meet demand, or the use of energy-efficient equipment and automation systems, they have all made a difference in reducing the energy requirements within the flour milling operation,” said David Jansen, vice president of production for Siemer Milling Co., Teutopolis, Illinois, US.

Gwirtz said the soft-start motors, which gradually are brought up to full speed, operate in stark contrast to the motors that were in mills when his career began in the late 1970s.

“If you’ve ever watched an amp gauge on a hammermill when it starts up, at least on the older ones, the needle on the amp just flies forward,” he said. “The amp load on the motor was probably 200 horsepower but the initial rush was probably 7 to 9 times greater than the full load. It wasn’t just a slight overload, it was a major, major overload.”

Milling companies also have found savings by replacing fluorescent light bulbs with LED lighting and adding motion-detection sensors that automatically turns off lights in areas where employees aren’t working.

You might also enjoy:

Electronic trading technology ended 150-plus years of open outcry buying and selling and has potential to transform the grain elevator’s role.

Whether increasing production line capacity or reducing plastic waste, sealing in freshness remains at the heart of packaging.

Legislation, science and culture have all been variables in the evolution of food and worker safety.

Improvements in efficiency

Today’s mills run more efficiently than ever, and the driving force behind that is automation. It has boosted productivity by allowing mills to operate around the clock, seven days a week with minimal or no personnel inside the plant.

“A good automation system has become the most important companion of the miller,” Birrer said.

The use of sensor technology has revolutionized milling and enabled problems to be detected more quickly than they were years ago.

A part of the mill’s control system, sensors acquire information that produce data that can be used to analyze the overall mill performance and optimize the performance of a specific piece of equipment. They let millers know when bins are full or when bearings are overheating as well as measure product quality, enabling automatic adjustments to be made without shutting down the mill.

“The sheer amount of data and information we have available at our fingertips today is amazing,” Jansen said. “When I first entered the industry, I would hear people say that milling is an art, and I would say that today it’s evolved and is still evolving into a precise science. When you look at what we can monitor, compared to 30 years ago, it’s pretty remarkable.”

The benefits of automation to the milling industry have evolved and grown over time, Anderson said.

“In 1992, automation was about labor savings and energy savings,” he said. “Today, we talk about automation to drive food safety, such as being able to trace product through the entire process.”

The future of milling

Given some of the dramatic technological advances that have taken place in the last 100 years, many of which couldn’t have been forecast a century ago, it’s difficult to imagine what lies in store for the milling industry over the next 100 years. One thing that’s certain is there will continue to be an increase in data collection related to every aspect of the milling operation.

“Our vision leads us to imagine a milling industry where the collection and management of data will be increasingly more relevant, making it so that all decisions are based on data collection and subsequent processing,” Galli said. “The data will guide us through milling management and compliance with parameters. Today, we already have plants where it is possible to change the settings of the roller mills, or reposition the products inside the technological flow, fully automatically, based on information received from the field, and their relation to the filed data.

“The data will give us information on what raw materials to buy based on what finished products needs to be produced in the short and the long term, all with the possibility of integrating this information with strictly updated market prices. Basically, the data will guide us to make the best choice based on the situation that has developed, all in real time, because that will be another crucial aspect. These aspects are then linked to the use of new design tools, of both machines and plants, to optimize costs as well as production times, always guaranteeing the maximum quality over time.”

Birrer predicts that traceability and sustainability — issues that have recently become high priorities in the global milling industry — will remain “hot-button” issues in the future and solutions will continue to be developed to address mill performance in these areas.

“Blockchain technology may be used to track the product from farm to fork,” Birrer said. “Also, the CO2 footprint will become a key sustainability indicator of milling companies, putting pressure on the whole grain value chain including grain handlers, millers, bakers and the respective solution providers to make their processes as efficient as possible. Digitalization will play a major role in this transformation.”

Gwirtz believes an increasing number of customers will demand transparency when it comes to knowing details about every step in the flour production process, from where the wheat was grown and harvested to all the steps thereafter that are involved in creating the final product.

He believes milling companies are “going to get pressure to pay more attention than ever to what goes through their milling units” and that more milling wheat will be purchased directly from the farmer.

While Anderson agrees that in the short term the trend toward farmer-direct wheat purchases will continue to grow, he foresees technology revolutionizing how the wheat kernel’s journey from farm to fork is documented.

“With the right technology, we will be able to provide the same traceability and the same ability of knowing exactly where that kernel of wheat was grown, whether it comes to us directly from the farmer, from a terminal or a country elevator,” Anderson said. “That’s where the technology has to go. I still believe there will be a fundamental place for the grain elevator in the supply chain to be a part of our industry.”

Likewise, Jansen foresees great strides being made in reducing the microbial load in flour as demands from consumers and regulatory agencies increase.

“I think the expectation will be that all flour is food safe — ready to eat,” Jansen said. “The industry will continue to look for solutions to meet these demands, whether it’s treating wheat during the tempering process or treating flour after it’s milled. I think eventually all flour will be treated in some fashion to make it food safe. A lot of work is currently being done to come up with a solution.”

He noted that Siemer Milling has installed two heat treatment lines for flour, bran, and germ to produce both food safe and functional flour products.

In terms of grain storage improvements, Peter Marriott, sales manager for Satake Europe, a milling equipment manufacturer, foresees going beyond today’s ability to monitor ambient conditions during storage.

“In the next step, imagine if storage silos will be able to fully adapt themselves to the changing ambient conditions, with receiving real-time weather information from the internet,” he said. “This example can be extended to other processes in order to explain how we achieve optimization and food safety with technology implementation.”

Specialty milling

The current trend toward increased specialty milling will continue to gain momentum, Anderson predicted, as he sees a shift away from almost exclusively milling traditional “white fluffy flour.”

“I see the industry shifting toward organics, which has become a larger segment for us, as well as a shift to milling ancient grains, legumes and other alternative proteins,” Anderson said. “As flour millers we can be too wrapped around a kernel of wheat. Wheat will always be a core and fundamental aspect of our industry. However, we have to continue to look at other products that are nutritious and provide a good alternative protein. At the end of the day, it’s about what consumers want and we need to explore how we can partner with customers to supply those.”

Anderson said Ardent Mills was positioned to be a provider of plant-based protein solutions through dry milling of various pulses and legumes.

“We’ve learned during the last several years that there are a lot of similar technologies in play, and it requires a lot of the same expertise that we already have with wheat milling,” he said. “We feel very good about our capabilities and our ability to serve those demands.”

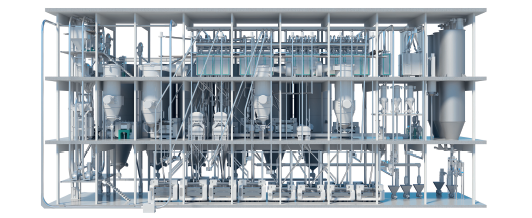

Milling equipment manufacturers agreed that the mill of the future would likely be smaller.

“We definitely expect to see more compact milling systems in the future,” Marriott said. “With an efficient plant design, combined functions of machines, and simplified processes, we will develop smaller plants with optimal usage of the area, and a lower energy consumption advantage as well.”

Galli said he envisioned mills being shorter in height than many of today’s 6- or 7-story buildings thanks to alternative plant engineering concepts, the type that Ocrim began working on more than 50 years ago. He noted that some of these concepts are “already applied today, that make it possible to eliminate at least two floors in comparison to a traditional mill.”

While the square footage is likely to decline, production capacities at individual plants will continue to increase as it becomes harder for smaller flour mills to compete.

“There’s certain fixed costs, whether it’s a 5,000- or 10,000-cwt mill, that are always going to be there,” Jansen said. “So, the economics of it are going to continue to drive larger milling units and/or larger mills with multiple milling units within them just to capture those efficiencies of scale.”

Anderson also sees a future with fewer but larger-capacity flour mills.

“It’s hard to spend the millions of dollars needed to continually upgrade a 5,000-cwt mill versus the economy of scale you get with the bigger mills,” he said. “That’s the fundamental shift we keep seeing. Whether it’s within a given company or with mergers, I do think that’s probably a trend that’s going to continue.”

The future of milling: art versus science

Over the years but especially in recent decades as technological advances in the milling industry have accelerated, a common topic of debate among millers has centered on the question: To what degree is milling an art as opposed to being a science?

And as milling plants become more automated with huge volumes of real-time data available to analyze every conceivable aspect of the operation, is flour milling becoming less of an art?

“Absolutely, it has become less of an art,” said Merzad Jamshidi, chief executive officer and managing director of KFF Mills, Tehran, Iran.

“The only part where it still remains a bit of an art is how millers mix and match their raw material to produce the ideal product,” he said. “Milling is like any other business. You look at the aviation industry where the emphasis is more dependent on automation and less on pilots’ input and performance — I believe the mills are also heading the same direction.”

Still, many millers are adamant that despite mills being equipped with state-of-the-art automation technology, the human senses of millers still have a major impact on how successfully a mill operates.

“It is absolutely still an art,” said Troy Anderson, vice president of operations at Ardent Mills. “The technology provides quicker validation that the art is on target. We still need our millers, and they still need their sense of touch, sight, smell and sound to set up our mills and to know when we have an issue. At the same time, we have a lot of great technology that is getting better at beating those senses to solve the problem.”

Milling industry consultant Jeff Gwirtz, president of JAG Services Inc., and a former milling science professor at Kansas State University, said he feels strongly that even though computer-controlled systems have enabled millers to start a mill with the push of one control-room button rather than a series of buttons located on different floors of the plant, it is still important for the milling operative to understand the logic behind the series of events that unfold when a mill ramps up.

“Even though you push a button to start the systems, you should be able to sit in the control room and say, ‘I know this system is starting because I pushed the button and not only do all the lights turn green along the way, but I can hear it start up,” Gwirtz said.

“Sometimes you need to tie the pushing of the button to a series of events that should have to occur that have a practical and physically observable evidence of happening other than just the green light going on.”

The same goes for when a problem is occurring in the mill.

“If you have to wait until an alarm goes off and a red light flashes to understand you’re having a problem, then you weren’t running the system, the system was running you,” Gwirtz said.

David Jansen, vice president of production for Siemer Milling, said the advances in automation, particularly regarding data collection, have helped millers spend more time on the parts of the job they enjoy most.

“I don’t think the art is gone and I absolutely believe the need for the miller is still there,” he said. “I’d like to think that the advanced technology is helping millers today do more milling and less of the mundane tasks.”

Perhaps someday Artificial Intelligence (AI) will progress to the point where the human touch of a miller is no longer of value. But most agree it will probably take many years for such a scenario to play out, if ever.

“Every wheat kernel is different, just like every person is unique, and we have to have people who are good at responding to that,” said Anderson, a 30-year milling industry veteran. “To a degree, AI someday may be able to do that but we’re nowhere close to that today, so being good at marrying the art with the science around technology — we feel that’s the sweet spot of being really effective at what we do.”

Even the manufacturers of the increasingly automated equipment used in today’s mills foresee trained millers remaining as a valuable part of the milling operation in the years to come.

“The concept of the art of milling will certainly change and therefore also the way today’s millers are used to working,” said Marco Galli, technological manager at Ocrim. “There will be an increasing comparison of numbers because the data will be what guides and supports millers in their choices every day.

“Imagine the potential that could be achieved by combining the experience of a miller with data collection and the relative analysis of this data, for example, in managing the energy consumption of milling based on the wheat mixing. What I see in the future of the miller is the capacity to optimize the processes using supporting information made available through the collection and processing data from the field.”