By Jeff Gelski

October 19, 2021

A diet for digestion issues

gains traction globally

Studies show effectiveness of low FODMAP diet, but grain-based foods restrictions pose challenges.

©sonyakamoz – STOCK.ADOBE.COM

Created at the onset of the 21st century, the low FODMAP diet focuses heavily on improving digestion, a trending topic, which gives the diet a bright outlook as the century unfolds. In contrast to fad diets, which often gain popularity in the complete absence of supportive scientific research, published studies about the low FODMAP diet continue to show its effectiveness. It helps with issues such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which affects one in seven consumers globally, according to Monash University in Melbourne, Australia.

“They are typically people that are just miserable when they eat certain foods,” said Julie Stefanski, a registered dietitian nutritionist and spokesperson for the Chicago-based Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. “The goal of this diet is really to alleviate different digestive symptoms that happen when people eat certain foods.”

A drawback comes in the diet’s complexity. Grain-based foods are allowed in the diet but in a limited role. Many suppliers are developing FODMAP-diet friendly grain-based ingredients.

The low FODMAP diet limits foods that have been shown to irritate the gut and cause irritable bowel symptoms like bloating, gas, constipation and diarrhea. FODMAP stands for fermentable, oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols. The diet affects numerous food and beverage categories, including baked foods. Fructans, which are in wheat, barley, rye and inulin, are oligosaccharides.

The diet’s origins

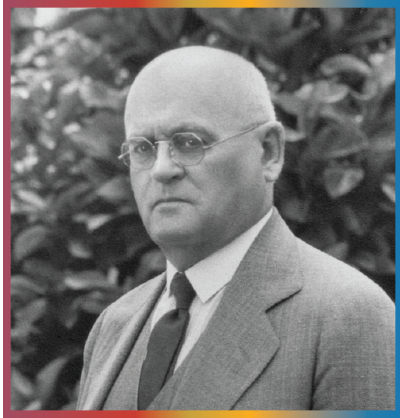

Researchers at Monash University created the low FODMAP diet in 2005. Peter Gibson, PhD, a professor in the Department of Gastroenterology, recruited Jane Muir, PhD, a dietitian-scientist who had worked with resistant starch and non-starch polysaccharides, and Susan Shepherd, PhD, a dietitian known for her work with celiac disease as well as fructose malabsorption and gut symptoms.

“We had all played with various things, like reducing fructose and manipulating fiber,” Dr. Gibson said. “A few of us came together probably at the right time. Jane and I had both been in the fiber area for a long time.”

Before the low FODMAP diet, treating IBS involved focusing on one subject, like fructose, fiber or lactose, Dr. Gibson said.

“What the term FODMAP did was to bring all these things that did similar things in the gut together,” he said.

The researchers at Monash University developed the diet over a year or two, Dr. Gibson said.

“The principals were there, but it was all based on very poor data,” Dr. Gibson said. “The big turning point was when we started to get some science into it.”

Published research on the diet has picked up over the past few years.

A study published in 2016 in the World Journal of Gastroenterology found 86% of 180 patients with IBS or inflammatory bowel disease reported either partial (54%) or full (32%) efficacy. The greatest improvements came in bloating at 82% and abdominal pain at 71%. Median follow-up time was 16 months. The study involved researchers from North Zealand University Hospital in Denmark.

The following year another study was published in the World Journal of Gastroenterology. Researchers from the University of Otaga in New Zealand divided participants into two groups. The first group, with 23 participants, began a low FODMAP diet. After three months they had significantly lower IBS symptoms than the 27 participants in the second group, which then began following the low FODMAP diet while the second group began reintroducing foods into their diet. Reduced IBS symptoms were sustained at six months in group one and replicated by group two.

Much has been learned about the diet since then, said Michael Schultz, PhD, one of the study’s authors and a professor at the University of Otago.

“The low FODMAP diet has been a breakthrough in the treatment for irritable bowel syndrome,” Dr. Schultz said. “Recent research is assessing the effect of the low FODMAP diet for other indications such as inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulosis, etc. Further research into the mechanisms is also on the way.

“Research into the cause of diseases was initially based on genome-wide association studies, but when this proved to be of little daily clinical consequence, the focus shifted to microbiome research. Over the last few years, a close link between the intestinal microflora and a variety of diseases has been observed. This is not just limited to gastrointestinal diseases but encompasses cardiovascular, neurological, metabolical diseases as well.”

In 2019, a study published in the International Journal of Food Microbiology and involving Monash University researchers examined gluten sensitivity and FODMAPs. While about 1% of the population has celiac disease and must avoid gluten, another 10% to 15% report a wide range of gastrointestinal symptoms that respond well to a gluten-free diet, which is called non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS), according to the study. Monash University researchers identified other factors in gluten-containing foods that may be responsible for those diagnosed as having non-celiac gluten sensitivity.

“We have evidence that certain poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates (called FODMAPs) present in many gluten-containing food products induce symptoms of abdominal pain, bloating, wind and altered bowel habit (associated with irritable bowel syndrome, IBS),” the researchers said. “Our research has shown that FODMAPs, and not gluten, triggered symptoms in NCGS. Going forward, there are great opportunities for the food industry to develop low FODMAP products for this group, as choice of grain variety and type of food processing technique can greatly reduce the FODMAP levels in foods. “

The validity of non-celiac gluten sensitivity was questioned in a cross-sectional survey of 147 patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Seventy-five percent reported improved gastrointestinal symptoms on a gluten-free diet, but researchers observed celiac disease had not been excluded adequately in 62% of the patients, 24% experienced uncontrolled symptoms despite gluten restriction and 27% said they were not following a gluten-free diet.

“These findings typify a common scenario in clinical practice, whereby patients present with a self-diagnosis of gluten intolerance without adequate exclusion of celiac disease or other gastrointestinal disorders and, in many cases, experience ongoing symptoms despite strict adherence to a gluten-free diet,” the researchers said.

Researchers now understand the mechanisms by which FODMAPs induce gut symptoms, and Monash University has built a large database describing the FODMAP composition of food, said Jane Varney, senior research dietitian in the Department of Gastroenterology at Monash University. She added future research will focus on the efficacy of a low FODMAP diet in people with other conditions such as endometriosis (a painful disorder in which tissue grows outside the uterus), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and functional gastrointestinal symptoms; efficacy of a low FODMAP diet compared to other effective treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy and anti-depressants; implications of changes in microbial abundances on colonic health; the extent to which changes in microbial populations can be rectified using dietary liberalization; the efficacy of a low FODMAP diet in children with IBS; the role of new FODMAPs , including xylose and arabinose, and sucrose and dextrins, which in some people with IBS may trigger symptoms; and the efficacy of other modes of delivery of FODMAP education with examples being telehealth and group education sessions.

Reintroducing foods

The diet involves three steps. First, those with IBS and other digestive problems follow a strict low FODMAP diet, taking out all the elements that might cause problems. If symptoms improve, they move to a second step, which involves adding back in elements one by one.

“It’s meant to narrow down the exact food that may be triggering your problems,” said Pamela A. Cureton, a clinical and registered dietitian and a member of the Grain Foods Foundation’s

scientific advisory board.

In the third step, the diet becomes personalized. Work continues with a dietitian.

“It’s really a learning diet,” Dr. Muir said. “That’s how we like to describe it. People are learning which particular FODMAPs trigger their symptoms because everybody is different as to which FODMAP diet will be proper for them.”

Dr. Gibson added, “The beauty of this diet is we don’t get rid of any food groups or nutrients. It’s a matter of choosing the right foods and the food groups.”

Reintroduction of foods into the diet was addressed in the study published in the World Journal of Gastroenterology in 2016. Eighty-four percent of patients lived on a modified low FODMAP diet where some foods rich in FODMAPs were reintroduced, and 16% followed the diet without deviations. Wheat, dairy products and onions were the foods most often not reintroduced.

A study published in 2017 in Neurogastroenterology & Motility and involving researchers from King’s College in London also addressed reintroduction of foods. Among 103 participants who originally had irritable bowel syndrome, 84 stayed on a low FODMAP diet long term while 19 returned to a habitual diet. The study identified low FODMAP food products appropriate for a low FODMAP diet, with gluten-free bread being an example, and high FODMAP food products. Total FODMAP intake was significantly lower for those on the FODMAP diet (20.6 grams per day, plus-or-minus 14.9 grams) when compared with those who returned to the habitual diet (29.5 grams per day, plus-or-minus 22.9 grams). Participants who stayed on the low FODMAP diet consumed significantly less onion and garlic.

Breaking the findings down into categories, participants who stayed on the low FODMAP diet consumed a higher intake of low FODMAP bread, 27.04 more grams per day when compared to participants who returned to a habitual diet. Those on the low FODMAP diet ate 26.7 less grams per day of high FODMAP pasta when compared to those who returned to a habitual diet.

Those on the low FODMAP diet may consume some grain-based foods, but fermented foods should be avoided.

“When you have fermentable foods, they are very good for human health, but for people with irritable bowel syndrome, if something is fermentable, it means that it’s going to cause those digestive symptoms like bloating and gas that can be very painful for people,” said Julie Stefanski, a registered dietitian nutritionist and spokesperson for the Chicago-based Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

Sourdough bread may work in a low FODMAP diet because a long proofing process breaks down fructans, Dr. Gibson said, adding spelt also is lower in fructans.

In the study published in the International

Journal of Food Microbiology, Monash University researchers found sourdough cultures in breadmaking reduce the quantities of FODMAPs, mostly fructans, which results in bread products that are well tolerated by consumers with IBS. Greater interaction between biomedical scientists and food scientists could improve the understanding about the clinical problems consumers face and lead to the development of food products that are better tolerated by this group, according to the study.

Other low FODMAP bread and cereal products include corn flakes, oats, quinoa flakes, quinoa/rice/corn pasta and rice cakes, according to Monash University.

Gluten-free foods potentially may work in low FODMAP diets as well since fructans and gluten often are in the same types of food. Ms. Stefanski said the keto diet differs from the low FODMAP diet in that the keto diet looks at the amount of carbohydrates but not the type of carbohydrates. Low FODMAP involves the types of carbohydrates consumed.

Researchers are working on ways to reduce fructan levels in food through the use of enzymes, said Kiarra Martindale, a dietitian and the business development and marketing manager for Melbourne-based FODMAP Friendly, which offers a certification trademark for products that qualify as low FODMAP. If the research is successful, “that’s going to be a game-changer in the FODMAP space,” she said.

You might also enjoy:

Volume changes have been seismic, while origins and destinations have fluctuated and will continue to do so as new disruptors emerge.

Overcoming complexity

Consumers may have trouble succeeding on the low FODMAP diet if they try it on their own.

“The problem is, it’s difficult to follow,” Ms. Cureton said. “It’s difficult to understand. You really do need the help of a trained, knowledgeable dietitian.”

Ms. Stefanski said, “It’s rather a confusing mix of foods. Many people try to do this on their own without a dietitian, or somebody to guide them. You really need someone to guide you through this.”

Dr. Gibson was involved in a study published in 2019 in the Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology that stated the optimal delivery of the diet requires a combination of education in physiology, food composition and identification, reading of food labels, and a process of restriction of foods and then reintroduction. The study looked at simplifying the diet by examining a FODMAP-gentle approach in which a dietitian targets attention to the changes to each consumer’s individual intake and makes allowances for dietary flexibility, such as allowing more legumes for vegetarians. The study also addressed “fear-mongering” of the diet, or discouraging consumers from following the diet because of its difficulty. Practitioners, including gastroenterologists and dietitians, who do not advocate for the low FODMAP diet likely will discourage adherence, according to the study.

Researchers from Monash University continue to educate gastroenterologists, clinicians and dietitians.

“Before the pandemic, we would be in the US every year,” Dr. Muir said.

The food industry is learning about the diet as well.

“It has a very specific purpose, much like gluten-free,” Ms. Cureton said. “Gluten-free was designed for people with celiac disease and gluten-related disorders. FODMAP is well-studied in its use for people with irritable bowel syndrome to control abdominal pain cramping, diarrhea, constipation. It has a very specific use that it works very well in.”

Manufacturers need to be careful about promoting their products as FODMAP-friendly.

How to gain low fodmap certification

Two low FODMAP certification systems have been established in Australia and are available for food and beverage companies globally. Monash University in Melbourne, where the low FODMAP diet was created, offers one system, and the FODMAP Friendly Certification Program, based in Victoria, offers the other.

Susan Shepherd, PhD, a dietitian known for her work with celiac disease as well as fructose malabsorption and gut symptoms, was involved in the creation of the diet at Monash University. She then was instrumental in creating the FODMAP Friendly Certification Program. Tim Mottin, now director of FODMAP Friendly, more than a decade ago worked in digestive health clinics in Australia. His patients were frustrated by various digestive issues, like fructose malabsorption and lactose intolerance.

“We had all these patients saying ‘What do I do? I’ve got all these issues. What do I do? How do I eat,’” Mr. Mottin said.

He began working with Dr. Shepherd since he referred many of his patients to her. It took several years to qualify for a certification trademark from the Australian government. The FODMAP Friendly logo began appearing on food products in 2013. To qualify, each product is tested to have minimal levels of fructose, fructans, galactooligosaccharides, sorbitol, mannitol and lactose.

“It’s been massive growth,” Mr. Mottin said. “It started off slow because it was all about the education of it and the awareness of it.”

The logo now appears on more than 700 products globally, including some from The Manildra Group, Gladesville, Australia. A flour mill in Australia uses a chemical-free extraction process to remove FODMAPs (fermentable, oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols) from Manildra’s Australian-grown wheat.

More than 300 products in the United States have qualified for the logo. FODMAP Friendly works with the University of Michigan and William Chey, PhD, a gastroenterologist at the university.

Five steps to certification

Food companies and ingredient suppliers may achieve low FODMAP certification from Monash University by following five steps.

First, they need to establish a new account at www.monashfodmap.com. The second step involves completing and submitting an application form. The product will not be eligible if it contains garlic, onions or their derivatives, or added FODMAPS, including fructo-oligosaccharides, inulin, and the polyols maltitol, xylitol, erythritol, lactitol and isomalt.

Companies then send product samples for testing. Monash University researchers will work with companies to reformulate products and help them meet low FODMAP criteria. In the fourth step, approved products become eligible to join the Monash University Low FODMAP certification program, which includes a stamp of approval and trademarks on product packaging as well as promotional materials. The product also will be included in the Monash University FODMAP diet app. Step five concludes the process with launching of products with the certification. The app, unveiled in 2011, now is found in more than 130 countries.

Certified ingredient companies

Ingredient companies listed as having achieved low FODMAP certification include Ingredion, Inc., MGP Ingredients, Inc. and Roquette.

Ingredion, Westchester, Ill., offers Versafibe 1490 dietary fiber, which is derived from potatoes, and Novelose 3490 dietary fiber, which is derived from tapioca. Both ingredients are classified as resistant starch type 4 (RS4). The low FODMAP certified ingredients allow manufacturers to add fiber to food with little to no impact on texture, flavor and color, said Diana Nieto Velez, senior manager, businessdevelopment, starch-based texturizers for Ingredion.

Ingredion’s August 2019 study of more than 750 US consumers found that, when introduced to low FODMAP product lines, 68% said the products were good for digestive health and 53% said they would be very likely to purchase low FODMAP products (based on a top-two box score of “agree” and “strongly agree”).

MGP Ingredients, Atchison, Kan., has received low FODMAP certification for its Fibersym RW and FiberRite RW ingredients. The resistant wheat starch ingredients are sources of fiber used in processed foods such as bakery, pasta, snacks, breakfast cereal, and batter and coatings.

“With the increased awareness of low FODMAPs diet and the challenges in developing low FODMAP foods in cereal-based products, we see increasing demand for our products being used in low-FODMAPs formulations,” said Tanya Jeradechachai, vice president, ingredient solutions R&D.

MGP Ingredients promotes the low FODMAP certification through webinars, conferences, journal articles, marketing brochures, sales sheets, interviews and social media, she said. The highest interest in low FODMAP certification comes in the United States, Canada and Australia, she said.

Comet Bio, which has its US headquarters in Schaumburg, Ill., is seeking low FODMAP certification for Arrabina, an arabinoxylan prebiotic fiber upcycled from wheat crop leftovers. The fiber’s long-chain polysaccharide structure makes it better tolerated by the gut compared to oligosaccharides, said Hannah Ackermann, a registered dietitian and corporate communications manager for Comet Bio. The company’s recent clinical trial revealed consumers can eat more than 12 grams of Arrabina per day with no negative gut or bowel reaction.