By Laurie Gorton

March 2022

The processing

perspective

By covering the ‘noisy part’ of pet food production, the magazine offers readers insight not previously available.

Pet foods of the 21st century are almost nothing like those of the 20th century. They differ in ingredients, packaging, processing technology and nearly every other production aspect. Pushed by pet owner demands, the industry has brought its standards up to those of foods made for human consumption.

How to satisfy those demands and achieve those standards is the challenge facing today’s pet food and treat processors. The ongoing assignment of one of the newest Sosland Publishing Co. magazines, Pet Food Processing (PFP), is to deliver insight that informs manufacturers’ and brands’ product development, processing and delivery. The four-year-old publication focuses on solid reporting in an industry with sustained growth for more than a decade now.

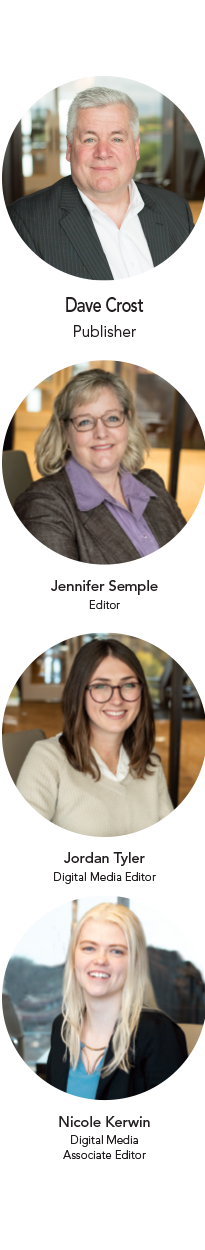

“Each Pet Food Processing issue contains a plant story, an equipment story, an ingredient story, a packaging story and a food safety story,” said Dave Crost, publisher of Pet Food Processing and MEAT+POULTRY. “That model has been successful for Sosland in the past and present; now, we are taking it to the future of the pet food industry.”

In other words, PFP describes what happens within the plant walls. According to Crost, this is an editorial approach not available from competitive sources. It makes PFP as unique as the nearly 600 new products that Mintel and Tree Top, Inc. report being introduced annually by the North American pet food industry.

According to the American Pet Products Association (APPA), total pet industry revenue reached an all-time high and totaled $103.6 billion in 2020, with pet food and treat sales leading the pack at $42 billion. This total represents a strong 6.7% increase from 2019 pet food and treat sales. From a retail perspective, across-the-board sales increases for every channel were recorded, with e-commerce coming out on top. In addition to the total retail sales growth, APPA reported pet specialty and independent retailers “experienced solid growth” despite disruptions caused by the pandemic.

“The pet food market has changed in very big ways,” Crost said. “When I was a kid, we didn’t put much thought into the nutrition we fed our pets. Today, pet owners are very attuned to the ingredients and health benefits of the food and treats they select for their pets. It amounts to a massive business.”

These dynamics occur because buyers of pet foods and supplies expect more out of the products they purchase for their pets. PFP’s March 2018 inaugural issue quoted the general manager of a major US pet food facility who said, “Pet owners want to buy the pet food which not only fits the exact nutritional needs of their pet but also caters to their personal ethics, beliefs and values.”

There are demands for convenience, traceability, sustainability, functional ingredients and clean labels. These factors dictate the content of PFP. The magazine’s management team adopted a production-centered format that had met with success for other Sosland publications.

“Our advertisers had been requesting that Sosland do something in the pet food field,” Crost said. “There was room in the market for this publication platform.”

In-plant and in-depth

Because production of pet food and pet treats crosses over animal feed and human food industries in multiple ways, articles about their technology and formulation occasionally ran in Sosland magazines, including Baking & Snack, MEAT+POULTRY, Milling & Baking News, Food Business News and other titles.

“Sosland Publishing has a long history of covering food manufacturing topics critical to producing safe, quality products,” said Jennifer Semple, editor, Pet Food Processing. “There is a fairly large overlap between human food processing’s ingredients, equipment, operations and food safety as practiced in the baking, meat, poultry and grain industries with operations in the pet food and treat industry.

“Bringing a pet food or treat product to market is extremely challenging,” Semple added. “Finding the suppliers and equipment manufacturers and experts to help processors through the challenges that their unique products create is key to success.”

Without Pet Food Processing, Semple observed, “Pet food processors must cover a lot of ground to find solutions that address their customers’ demands in this fractured and increasingly sophisticated market.”

PFP is editorial driven, as is every other Sosland publication. It strives to be a knowledge source for the formulation, production and safety of pet food.

The magazine’s mission is to provide in-depth information on pet food and treat processing news, technology and best practices, as well as to connect manufacturers of pet food and treats with the solution providers they need to produce safe, quality products. The magazine also reports the science driving innovation in the field, including university research.

Semple summarized, “We focus on being a resource to processors to help them keep tabs on how the industry, from a manufacturing perspective, is evolving so they can continue to meet their customers’ needs.”

She, Jordan Tyler, PFP’s digital editor, and Nicole Kerwin, PFP’s associate digital editor, strive to achieve a good balance between coverage of long-form, more in-depth topics in the quarterly print issues and daily digital’s more short-form sharing of the news impacting this industry.

All issues of PFP are available in digital format from the magazine’s website, www.petfoodprocessing.net.

Reader value verified

The importance of this editorial approach was borne out by the results of an internal reader survey taken by the magazine during 2021.

“We asked questions such as, ‘Should we increase frequency?’” Crost said. “The survey gave us the answer that our current quarterly schedule was the right balance.”

Other questions asked recipients to evaluate the editorial content as to its usefulness and relevance to the readers’ job responsibilities and about the publication’s digital offerings.

Since its launch in 2018, PFP has consistently outperformed its goals for digital engagement as well as for print subscriptions.

“Our survey respondents have given us high marks for our efforts so far,” Semple said. “Just comparing the first nine months of 2020 with the same timeframe in 2021, our web traffic is up more than 75%, and that has been a consistent pattern for us year-over-year since we launched.”

The newest change to the magazine will be the transition of its Resource Guide, a popular special issue published in October each year, to a comprehensive Buyer’s Guide.

“This gives our advertisers an additional opportunity to reach our readers,” Crost said.

For PFP, Sosland Publishing reported 7,550 average quarterly magazine circulation, 15,831 average digital alert recipients and 61,624 average monthly web sessions. All are 2021 numbers detailed in the 2022 PFP Media Guide. Crost shared circulation includes recipients in both the United States and Canada. Overseas requests for the magazine and its emails are handled on a case-by-case basis.

You might also enjoy:

By covering the ‘noisy part’ of pet food production, the magazine offers readers insight not previously available.

Magazine celebrates 40 years of covering the grain, flour milling and feed milling industries from an international perspective.

When Sosland Publishing added coverage of bakery technology in the late 1970s, it set the stage for today’s industry knowledge authority.

Supplier push

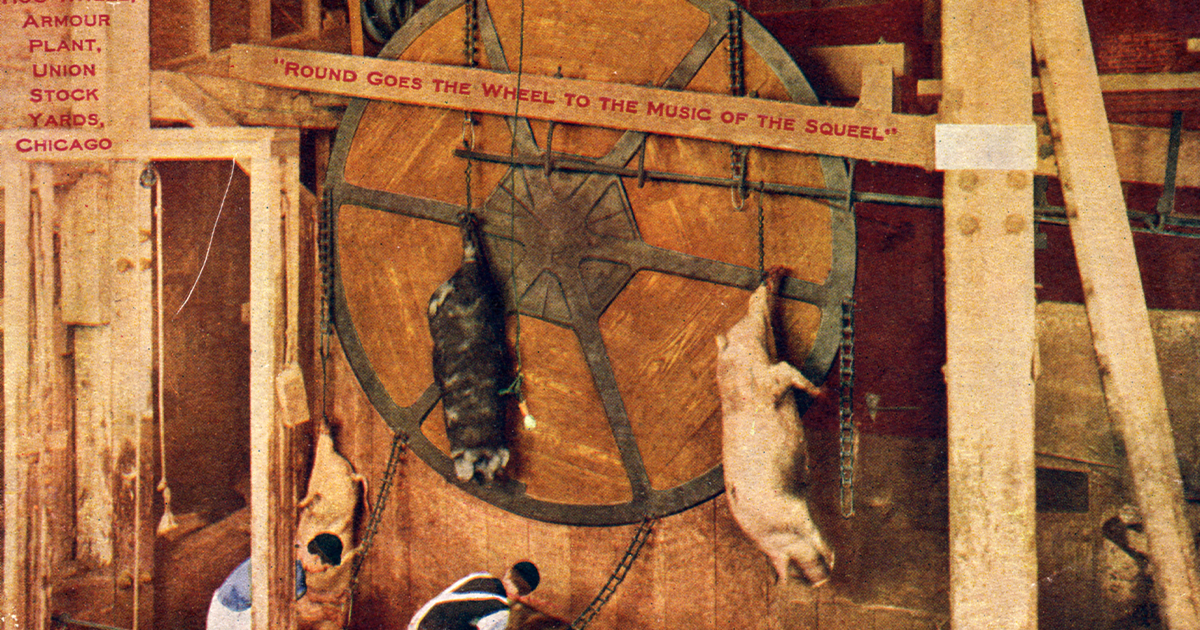

Sosland Publishing’s decision to introduce a pet food title fit its well-recognized and knowledgeable coverage of grain-based foods. In fact, the week before the company sent its first issue of PFP to the printer, a major food company, with deep roots in grain and flour milling, announced its acquisition of a large maker of premium pet foods. Today, the three largest pet food companies in the United States are all owned by major food processing companies.

For more than 10 years, the pet food industry has delivered growth that keeps investors’ tails wagging. APPA industry data indicates that the US pet food market has grown year over year since 2007 by at least 3.7% and as much as 10.7%. (PFP described the evolution of pet food from feed to food processing in its December 2021 issue.)

The magazine was launched in March 2018 as a quarterly publication. Its first issue carried a 96-page folio. The next year, it added a fifth issue, a Resource Guide, which documents the state of the industry, brand performance, processor profiles and other industry resources.

The idea of a Sosland magazine covering pet food processing first emerged in the 2010s. With the US economy still recovering from a steep recession, however, Sosland management hesitated to take on a new venture. As well, digital media were continuing to put print under considerable pressure.

Yet interest in advertising to this fast-growing field was evident.

“Several salespeople had accounts they believed would be interested in advertising in a pet food publication,” said L. Joshua Sosland, president, Sosland Publishing Co. “I sensed grassroots support for the idea across the sales staff.”

Crost described himself as a “chief cheerleader and convincer” for PFP. For some years, he frequently received requests from MEAT+POULTRY advertisers, especially the processing equipment vendors, for an advertising channel addressed specifically to pet food processors. So, too, had publishers of Baking & Snack.

“Our advertisers had seen an uptick in business from the pet food sector,” Crost noted. “At that time, these suppliers were not marketing directly to the pet food industry. The processes used by these manufacturers are similar to those in the meat and baking industries, and pet food processors told us they were reading magazines written for those industries to gain knowledge about technology, nutrition, food safety and packaging.”

Sosland Publishing Co. Chairman Charles Sosland described being approached by a number of the company’s publishers and top salespeople about a magazine covering pet food processing.

“We put the idea through the same due diligence we would have if we were acquiring a pet food magazine,” he said. “The concept developed traction and firm support from the top advertising prospects who were already advertisers in the Sosland universe. That really helped us move forward.”

Around this time, Crost and Charles Sosland hosted a dinner with the president of a major equipment vendor involved in this market. The executive explained that new business was being generated from pet food processors by word of mouth rather than any concentrated marketing efforts on the part of supplier companies.

“There were other conversations with vendors and with processors,” Crost said. “We asked, ‘If we build it, will you come?’ The answer was a very positive ‘yes.’”

With the corporate go-ahead, the next step was to assign sales managers and hire editors and columnists.

“We were fortunate to find Jennifer Semple to be our editor,” Crost said. “She has a background in business-to-business publishing, and Jordan Tyler, our digital associate editor, came on board with much-needed digital and social media skills.

“Once we got the editorial team together, things took off,” he continued. “Both editors have remarkable work ethics. From the beginning, Jennifer and Jordan reached out to our readers, advertisers and pet food and feed industry experts, including those at the university level. Jennifer has become well-recognized within the industry.”

The magazine is also served by a group of knowledgeable contributing editors and writers: Donna Berry, Jennifer Barnett Fox, Allison Gibeson, Keith Loria, Lynn Rogers and Richard Rowlands.

Change and stability

PFP demonstrated its solid business platform in mid-2020 when its publisher and chief salesman unexpectedly resigned. Four years earlier, the magazine debuted under the sales leadership of Steve Berne, publisher, and Adam Ungashick, lead sales representative. When both men left, Crost added the responsibilities of Pet Food Processing publisher to that of MEAT+POULTRY publisher. A number of senior Sosland publishers and salesmen, including Mike Gude, Bruce Webster, Troy Ashby, David DuPaul, Matt O’Shea, James Boddicker and Tom Huppe, stepped in to cover advertising assignments.

Crost explained that his role was to assure continuity.

“We did not experience any fall-off in our relationships with advertisers,” he said. “Everybody stepped up. We didn’t lose any business due to the personnel changes. It took a lot of work, true, but it turned out well. The market was sound. We were able to finish out 2020 in good shape, and we have had a successful 2021.”

Looking forward

The decision to give PFP a significant presence in both print and digital has been essential to its success. The magazine’s startup took place in a business-to-business publishing environment where print was losing favor to digital; however, Sosland has strong resources in both the print and digital channels.

“Pet Food Processing was our first launch in this era of social media and digital publishing,” Charles Sosland said. “The advertising mix is pretty close to 50/50 print/digital. PFP has embraced the opportunities that digital and social media offer, but we believe there is still a strong place for print going forward.

“Unlike some other publishers who have completely abandoned print, we believe the best way to deliver content is through all of the channels including print,” he continued. “But we have also embraced the digital and social media channels to serve a younger audience.”

Charles Sosland observed that the company has been actively engaged and investing in digital since the early 2000s. “Pet Food Processing is a little further along because its audience is a little further along, just as Food Business News is,” he said.

Semple explained, “We have to meet the reader where they choose to consume industry news, so we make an equally robust effort to deliver both print and digital content at a pace that fits well in the industry we serve. Having long-form content delivered quarterly allows us time to properly share that content in print and in our digital editions and through our website and social media channels to make sure that the information shared in our articles reaches the readers who need it.”

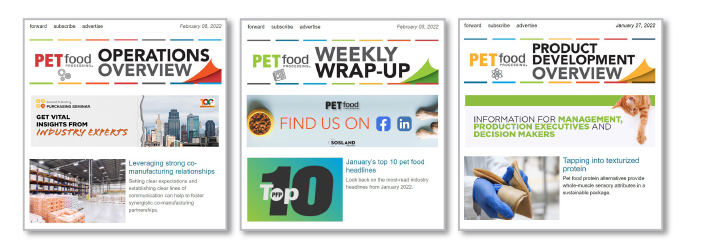

Offered through the magazine’s website, PFP digital products include email blasts, editorial videos, webinars and e-zines. Readers can sign up for e-newsletters: Operations Overview and Product Development Overview, both monthly reports, while Pet Food Processing Update is delivered semi-monthly, and the Weekly Wrap-Up is delivered every Saturday. The platform also offers custom publishing projects affiliated specifically with this magazine and the pet food and treat industry.

The company’s goal for PFP is steady long-term growth reflecting the diversity and continuous expansion in more sophisticated pet food products.

“We are confident that our growth will be equally divided between print and digital/social media, and that is what this market demands,” Charles Sosland observed. “We are also exploring the opportunity to serve the audience with a seminar devoted to pet food ingredient markets.”

Looking ahead, Semple said, “Like everything in life, it’s the people who matter most. Pet Food Processing’s greatest accomplishment, from my view, is the relationships we have built in the pet food and treat industry.”

She praised people’s generosity and openness in sharing what they know with others for the benefit of the industry. “And we’re honored to help facilitate some of that,” she added.

“Our star is rising,” Crost said. “Sosland brings grain, baking and the meat industry together. Pet Food Processing, which also brings grain, baking and the meat industry together, is a great opportunity to educate readers and serve the pet food industry.”