By Laurie Gorton

July 2022

Reporting from

the edge

Monthly magazine explores how, where and why supermarket innovations happen

Supermarket operators know that all the excitement happens today around the perimeter of the store. Now they have a publication that recognizes and celebrates such change: Supermarket Perimeter.

Introduced by Sosland Publishing three years ago, this monthly magazine and its digital products focus on the fresh operations that encompass circle the outer edges of grocery stores and supermarkets.

“Freshness, health, variety, flavor, innovation, authenticity, experiences — it’s little wonder that perimeter departments are getting the most buzz and generating the biggest sales increases,” wrote Andy Nelson, managing editor, Supermarket Perimeter and bake, in his Editor’s Note column for the magazine’s inaugural issue, January 2019. “We at Sosland Publishing have been hearing it for years.”

From corners to full perimeter

Supermarket Perimeter is exclusively focused on the fresh perimeter area of retail grocery stores. Its editorial teams cover the latest trends impacting the entire fresh perimeter and provide their expert insights on the news and trends impacting the perimeter’s key categories, including bakery, deli/prepared foods, produce, dairy, meat, poultry, seafood and more. The magazine also includes the popular Commissary Insider as a monthly supplement.

Troy Ashby, publisher, Supermarket Perimeter and bake, explained the evolution of the new standalone monthly magazine.

“Having served the grocery in-store bakery and in-store deli segment since 2005 with inStore Buyer and then inStore, we had a front row seat to see what was taking place in the perimeter area of grocery and were in a great position to expand our coverage to include insights for all fresh perimeter departments, including bakery and deli,” he said.

The move from inStore to Supermarket Perimeter was a natural next step. According to Ashby, the change was to fold coverage of the in-store bakery and in-store deli into the larger category of fresh. There were good market reasons for doing so.

Statistically solid positioning

“The evolution from inStore to Supermarket Perimeter largely was driven by the increased focus on and investment in fresh perimeter departments as a whole that grocery operations were making in the 2010s,” he added.

The Food Marketing Institute (FMI), the field’s leading trade association, continues to illuminate this trend with a series of webinars, podcasts and TED talks addressing Top Trends in Fresh. It noted that “retailers who are on the forefront of marketing and merchandising these products grow sales up to 25% faster than average.”

Earlier this year, FMI reaffirmed the importance of fresh: “Fresh food has had a phenomenal two-year run, with sales reaching an all-time high as people continue to eat at home and seek stores and meal ideas that meet their needs.”

FMI states that more than half of all supermarket sales involve perishables. It describes fresh as the ultimate disruptive grocery category.

“Fresh saw solid growth with even service-oriented departments like bakery and deli showing strong sales as both expected and surprising areas grew within fresh, leveraging the trends of health, fresh prepared/convenience, taste exploration and customization,” the group noted.

This trend continued despite the pandemic.

For example, a Supermarket Perimeter Daily email of April 19, 2022, reported: “Organic meat is booming. In the past year, organic meat sales have grown 37% vs. two years ago, outpacing the meat department, which grew 20%, according to Nielsen data.”

Such findings, reported over the past decade, paved the way for Sosland to launch Supermarket Perimeter. Ashby said that Rick Stein, FMI’s vice president of fresh foods, is one of the magazine’s authoritative sources.

“In our annual food industry speaks report, members tell us what’s going on,” Stein said in the March 2021 issue of Supermarket Perimeter. “And what’s happening in is stores are differentiating themselves in the perimeter. It’s a part of their key strategy.”

The importance of the perimeter is also emphasized by the International Dairy Deli Bakery Association (IDDBA), which recently described the importance of the fresh category by noting the proliferation of new channels, such as convenience stores and club stores, now competing with grocery.

Supermarkets still have built-in advantages that other channels can’t match.

“You’re not going to smell fresh bread being baked, you’re not going to see sandwiches or pizza being made, or the variety of cheeses or sampling,” according to IDDBA. “Fresh departments have greater roles now than they had decades ago.”

Audience and competition

Statistics about the audience of Supermarket Perimeter position the magazine as a premier marketing vehicle for advertisers serving the fresh departments of supermarkets.

Supermarket Perimeter is offered in both print and digital formats. It maintains active social media sites. It also offers a slate of digital products that include daily and weekly email newsletters, including Protein Insight Weekly and the monthly Perimeter Food Safety. Advertisers can also take advantage of customized webinars, targeted email marketing programs, white papers and e-zines.

The publisher estimates that advertisers have nearly 4 million opportunities annually to connect with their customers via Supermarket Perimeter and its affiliated properties. Print circulation for the monthly magazine averages 10,927 per issue, with digital circulation of 28,698 per issue. And the combined monthly newsletter circulation comes to 264,255.

Circulation by business class finds 78% grocery, supermarket, club; 11% commissary, central kitchen, bakery; and 10% distributor, broker.

“With inStore, we were already reaching c-suite titles, such as vice-president of perishables, director of fresh foods, etc. who had oversight of all fresh perimeter departments,” Ashby said. “So, the expansion to cover all fresh perimeter departments provided an even stronger media product for that portion of our audience.”

It is the only publication in the business-to-business field to focus exclusively on the fresh perimeter of retail food stores. In this, the magazine enjoys a distinctive competitive advantage.

“Supermarket Perimeter is unique in the fact that there isn’t a mirror competitor of the publication/media in the industry,” Mr. Ashby said.

Focused on fresh

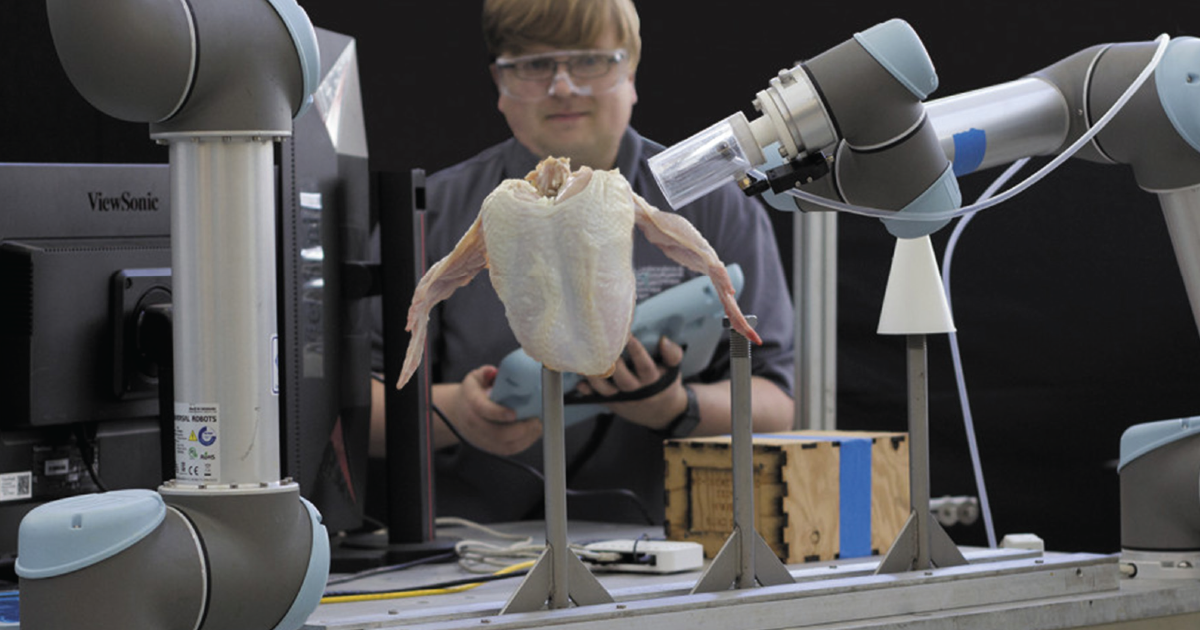

“We decided to transform InStore magazine, which covered just in-store deli and bakery, into Supermarket Perimeter because of the incredible growth throughout the fresh perimeter departments,” Nelson said. “Produce, meat and poultry and seafood are also making huge gains at retail. We also saw an under-explored opportunity: Supermarket Perimeter is the only trade publication that focuses exclusively on grocery fresh departments.”

John Unrein, editor, bake and Supermarket Perimeter, explained further. “Each month, Supermarket Perimeter delivers the insight and information bakery, deli/prepared foods, produce, dairy, meat/poultry and seafood executives and decision makers need to meet new challenges and capitalize on the opportunities in today’s dynamic market.”

“We want our work to give retailers practical ideas for ways to improve their fresh departments,” Nelson noted.

It’s a market willing to support both print and digital products. “Many of our readers still like the experience of reading longer-form pieces in our monthly print/digital editions,” Nelson said, “but the times are certainly changing, and we also need to cater to subscribers who want their news and analysis delivered more frequently and in easily digestible chunks.”

To celebrate the Sosland Centennial, Supermarket Perimeter has produced several articles discussing changes that occurred during the past 100 years in fresh presentation (March 2021) and preparation technology (November 2021). Others are planned to look at product development and predict future innovations for foods sold along the perimeter of grocery stores.

You might also enjoy:

Monthly magazine explores how, where and why supermarket innovations happen.

This innovative publishing platform now observantly reports about the changing face of retail baking.