By Kimberlie Clyma

December 2022

Looking

ahead

Overcoming obstacles and chasing innovation, the pet food industry prepares for its promising future.

©Quality Stock Arts –stock.adobe.com

While no one can predict the future, taking a close look at today’s evolving industry trends can give us a potential glimpse into where we’re headed.

The pet food industry has changed substantially from the time, almost 100 years ago in 1926, when Purina launched its first dog food — Purina Dog Chow. Now pet food and treat manufacturers offer complete-and-balanced meal options found in kibble form, freeze-dried varieties and even fresh pet food alternatives sold out of refrigerated grocery cases. Today’s formulations are no longer solely made from animal proteins and byproducts, but from plants, insects and even ingredients grown in laboratories. And pet food now provides more than the standard dietary nutrients dogs and cats require — they provide ingredients to help pets with cognitive function, mobility, mood enhancement and other life-improving activities.

Pet food is so much more than it was 100 years ago. And, while no one can predict the future, it’s safe say pet food will be so much more in 100 years to come.

The innovations that have been leading the pet food and treat industry over the past 10 to 20 years will be guiding the industry in the next 20-plus years, and beyond. Transparency, sustainability, automation, humanization and premiumization are trends that are shaping the industry and the key players within it.

“Companies either can embrace and innovate — or choose to resist change and lose relevance in the market over the next several years,” said Rick Ruffolo, chief executive officer and president of Phelps Pet Products, Rockford, Ill. “It’s the right thing to do for the industry, for our customers, and ultimately, for the planet.”

Challenging times

The US pet care industry is growing — and it’s growing at a rate beyond industry expectations. In 2020, the American Pet Products Association (APPA) reported that the US pet care industry reached a $100 billion milestone and was expected to grow an additional 6% in 2021. But the industry exceeded expectations and grew to $123.6 billion — a 13.5% increase. By all industry predictions, that growth will continue.

Growth will continue across all categories of pet care — $34.3 billion was spent on veterinary care and products in 2021; $29.8 billion was spent on pet supplies, live animals and OTC medication; and $9.5 billion was spent on services such as grooming, dog walking and boarding. But the most money in the pet care industry is spent each year on pet food and treats — $50 billion in the United States in 2021.

Despite the bullish outlook for the industry in coming years, it isn’t without challenges heading into the future — including ingredient sourcing, regulatory obstacles and labor shortages.

“Our challenge with innovation currently is really about ingredient sourcing — that could be a limiting factor to innovation in the future,” said Dana Brooks, president and chief executive officer, Pet Food Institute, Washington, DC.

Today’s ongoing supply chain challenges and concerns of future product shortages have led processors to look at ingredient sourcing through a more sustainable lens.

“There’s a lot of opportunities to explore upcycling,” said Seth Kaufman, co-founder and partner at Bentonville, Ark.-based BSM Partners. “We think the pet food industry has historically done a great job — much of it driven by costs — of upcycling byproduct-based materials into nutritious pet food.”

However, upcycling isn’t enough to meet the ingredient sourcing needs of the future. Alongside upcycling and utilizing ingredients not typically used for human food, the industry is looking to novel ingredients such as plant-based proteins, insect proteins and even lab-grown, cultured proteins to fulfill its ingredient sourcing requirements.

Berkeley, Calif.-based dog food company Wild Earth announced in October that it has developed a cellular-based meat broth topper for dogs, which, according to the company, will be the first cell-based meat product launched in the pet food industry. The company’s mission has always been to offer “clean” protein, nutrition-packed dog foods developed without harming any animals or the environment.

According to Wild Earth, 30% of the meat consumed in the United States is consumed by pets. The company aims to use its cell-based pet food products and other plant-based offerings to ease the environmental impact of sourcing traditional meats for the use in pet foods and treats.

“The shortage of protein is going to be the biggest challenge for the world going forward, whether it’s for humans or pets,” said John Kuenzi, chief executive officer and chairman, NQV8, Manhattan, Kan. “Protein that doesn’t compete with the human food supply is going to be a major component of future ingredient innovation. I think the ingredient streams for human and pet foods are going to become very competitive in the future. That should be at the back of our minds when we think about what’s truly sustainable for our planet.”

However, it’s not enough to just come up with new ingredients to incorporate into pet foods; getting these new ingredients approved for use in pet food products is where the true challenge lies.

“When we look at novel ingredients or any type of innovation in a formulation, our challenge goes back to the regulatory system that we operate that can hamper, prohibit and delay bringing in a new product to market,” Brooks said. “How can we get new innovative ingredients to market faster? It can take between five to 10 years from inception to formulation. We don’t want to shortchange the system to a point that we’re not creating safe or nutritious pet food, but technology and innovation is absolutely faster than the United States and state government, and that will be our limiting factor in the future.”

On Oct. 18, the US Food and Drug Administration held a listening session to hear opinions on updating the Center for Veterinary Medicine’s (CVM) Program Policy and Procedures Manual Guide 1240.3605. The American Feed Industry Association (AFIA) shared its position at the session, claiming that animal food ingredients that address animal wellness, food safety and production efficiency should be regulated as feed, not drugs. The current policy of regulating these ingredients as animal drugs is far more costly and lengthy and is interfering with new product innovation in the pet food marketplace.

“Updates to the policy would allow companies who manufacture animal food ingredients to appropriately market their ingredients,” said Louise Calderwood, director of regulatory affairs, AFIA, Arlington, Va. “In the pet food sector, we know there are ingredients that have positive impacts on cognition, mobility and mood for our pets. As pets are living longer and longer, the cognitive and mobility issues are becoming more and more important to consumers. Bringing these ingredients to market in the United States is absolutely essential for the many benefits they will afford our pets.

“As the claims issue gets resolved, we’re going to see such a breakthrough on the innovation side,” she added. “I’m very excited for the opportunities for the animal food ingredients to support our animals, so they can continue to be our active healthy companions.”

Aside from the regulatory hurdles that currently exist, the CVM is also underfunded and understaffed, Brooks said.

“It’s been challenging for the CVM to be able to recruit and retain talent,” she noted. “That’s one of our biggest challenges — making sure that the CVM is well funded in order to be able to hire the experts needed to get the work done.”

Anyone in the manufacturing industry knows, labor shortages aren’t reserved to the regulatory side of the industry. Pet food processing plants have been feeling labor pains for the past five years, and likely longer, with the COVID pandemic exacerbating the challenge even more.

“There are no pet food plants out there that are running as efficiently as they’d like to, because there is a definite workforce shortage,” said Tom Barrett, partner and vice president of business development and purchasing, Barrett Petfood Innovations, Brainerd, Minn. “I hear from other manufacturers all the time — where are the workers? Nobody wants to work.”

But some don’t see the labor shortage as being as simple as a shortage of workers.

“I think there is a labor shortage, but I don’t think the shortage itself is completely driven by a lack of labor,” Kuenzi said. “I think some of it is a case of people simply not wanting to do certain jobs anymore.”

St. Louis-based Purina PetCare has a manufacturing network consisting of 22 facilities in 15 states. A processing operation of that size takes a large workforce that needs to be trained and retained in order to maintain productivity.

“We work to develop and solidify relationships with trade and tech schools to showcase modern manufacturing as a viable and rewarding career path,” said Joe Toscano, vice president of trade and industry development for Purina. “These partnerships center around helping students better understand and embrace digital operations and technology that is a critical, yet sometimes unexpected, element of today’s manufacturing careers. Hiring and retaining top talent in our factories starts with helping potential associates envision themselves at Purina and embrace our culture and values, and then offering viable paths to development and career growth.”

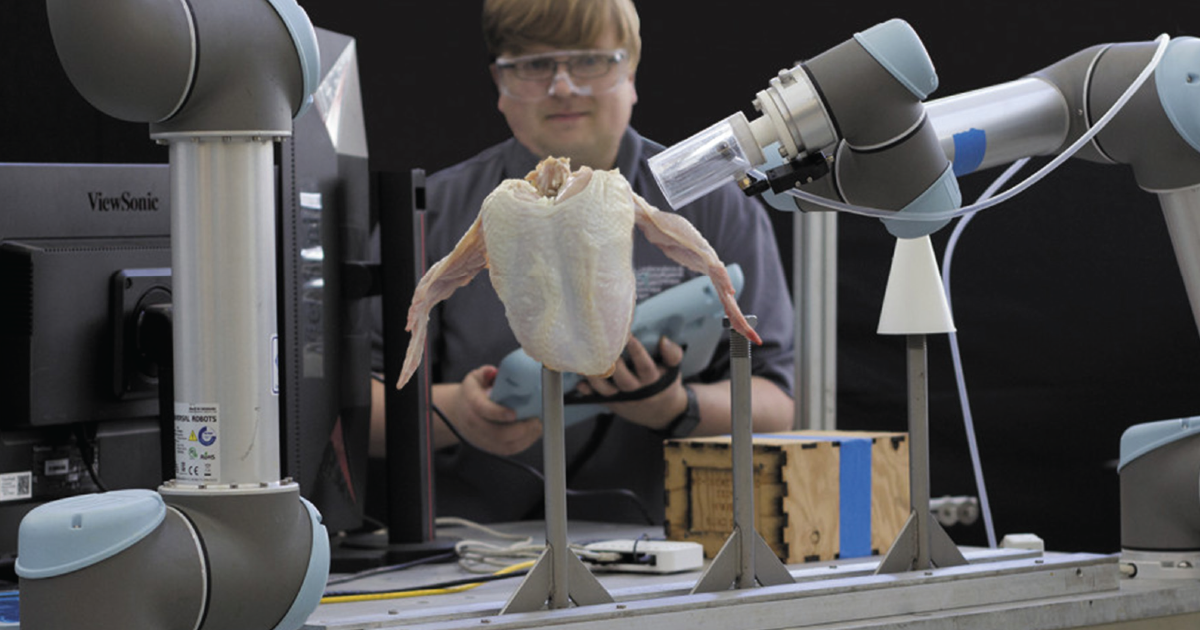

Digital operations, technology and automated systems are the future of pet food processing. Artificial intelligence will also be more common on the manufacturing floor, Kuenzi said.

“A lot of the things that we thought would never be done by computers or machines are starting to be done by them right now,” he shared. “I think there’s going to be more of a combination of labor. We’ll automate a lot more manual jobs in the future.”

As a pet food processor, Barrett is looking to automated systems to improve his current and future processing facilities. Barrett Petfood Innovations will soon open a new freeze-dried plant in Little Falls, Minn. The new facility was designed with “efficiency and innovation” in mind.

“We live in a world now where automation is available to us. It’s become really efficient and much more cost-effective,” Barrett said. “The next wave of manufacturing will definitely feature a lot of automation. We’re not necessarily trying to replace workers, but we’re using a different type of skillset and we’re making our operations more efficient. Anybody in our industry who’s not fully looking toward automation is way behind the eight ball.”

Staying sustainable

What started out years ago as an industry buzzword, sustainability has turned into an ongoing mission for suppliers and manufacturers throughout the human and pet food industries. Pet food and treat processors keep sustainability top of mind throughout a range of decision-making processes, from ingredient selection to plant construction and design to packaging choices and alternatives. Sustainability is decidedly here to stay and will continue to guide the industry well into the future.

“When we first started talking about sustainability a couple of decades ago, it was certainly focused on environment. But now, sustainability covers everything from packaging and environment to workplace inclusion and business organizational values,” Brooks said. “It’s such a broad swath of things. I think we’re going to see a lot more growth in sustainability, but we’re not going to be able to whitewash it.”

Processors in the industry concur. The quest to become more sustainable now and into the future is guiding a number of operational decisions. At Barrett Petfood Innovations, Barrett is constantly looking for ways to be more sustainable.

“Our operations and innovation for the future are turning more toward sustainability and less waste. As a co-manufacturer, that’s where we focus our operations,” Barrett said. “We are continuing to ask ourselves: How can we change our operation to have a little less of a [environmental] footprint? How can we make the same amount of food with less waste? With our packaging, how can we make more of a sustainability play? We are continuing to look for more efficiency through our manufacturing.”

CRB, a Kansas City, Mo.-based provider of sustainable engineering, architecture, construction and consulting to the food and beverage and life sciences industries, took a close look at the pet food industry’s journey toward sustainability in its Horizons: Pet Food report, released last April. The report showed sustainability as a top priority among pet food and treat producers. A survey question about future plans for becoming carbon neutral showed that the majority of the respondents’ companies either have plans in the works for becoming carbon neutral, or they soon will. Fifty percent will have a plan in place within five years; 30% within 10 years; and 7% in 10 years or longer. Only 6% of respondents reported that they have yet to start working toward this goal.

While carbon neutrality and other big picture environmental impacts are long-term goals for large pet food processors and smaller players alike, smaller sustainability initiatives are being pursued right now. A continuous push toward adopting more sustainable packaging is occurring across the industry today and will undoubtedly continue into the future as more options become available to processors. Processors are demanding recyclable, compostable and refillable packaging options from packaging suppliers.

“Packaging is the logical starting point to work on for sustainability,” Brooks said. “The challenge that we have to keep in mind is, we want the packaging to be sustainable and to be recyclable, but we have to make sure, first and foremost, that the pet food in that packaging stays stable and free of contaminants — that it’s in the best packaging for your pet’s food. There’s still a lot of work to be done in that arena.”

While its member companies are typically pet food processors, Pet Food Institute invites equipment, packaging and ingredient suppliers to be associate members of PFI to encourage industry collaboration.

“It’s a great way for us to make sure we are all collaborating on ideas and technology in order to move toward a common goal of providing safe and healthy pet food,” Brooks said.

Today, more than 80% of Purina’s product portfolio by weight is packaged in recyclable materials.

“We are working to optimize our packaging with the goal of making all of our packaging reusable or recyclable by 2025,” Toscano said. “We are also working to incorporate more recycled content into our packages and eliminate unnecessary materials. The aluminum cans that our wet dog and cat food come in can be recycled endlessly, resulting in a significant decrease in waste. In fact, recycling 75% of all aluminum cans would prevent 11.8 million metric tons of CO2 emissions.”

Nicole Suteau, corporate responsibility manager, Champion Petfoods, Edmonton, Alberta, added, “While we are always reviewing new ways to improve our environmental impact at Champion, we’re focusing on three key areas that will deliver meaningful progress to the industry in the long term, including sustainable and recyclable packaging, responsible ingredient sourcing, and reducing our waste to landfills.

“As other pet food manufacturers start taking on a more concerted effort to reducing their own ecological footprint, we feel confident that the industry can collectively come together to overcome many of the challenges we see in sustainability in the next 10 to 20 years,” she said.

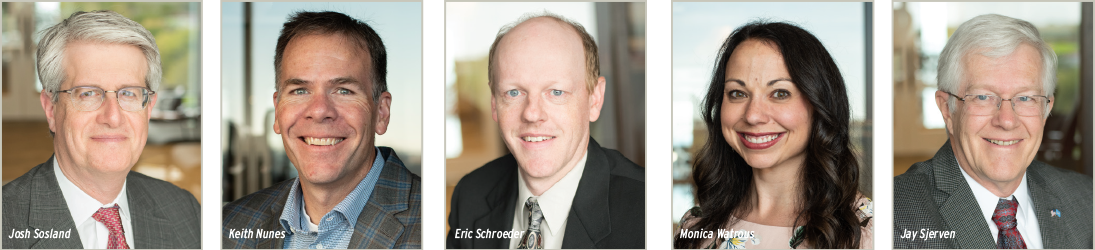

You might also enjoy:

Business intelligence and market analysis address the needs of readers throughout the food processing industry.

Sosland Publishing’s new publication offers insight into a dynamic industry.

Monthly magazine explores how, where and why supermarket innovations happen.

Evolving consumer

According to the 2021-2022 APPA National Pet Owners Survey, there are pets in 90.5 million homes throughout the United States. Millennials are currently the largest group of pet owners (32%), followed by baby boomers (27%) and Generation X (24%). With this younger demographic of pet owners comes a changing pattern in purchasing behaviors. Alongside the internal industry push toward sustainable packaging and other systemwide initiatives is the ongoing external nudge from many pet parents who are making purchasing decisions with sustainability in mind.

“We know that Millennials own more pets than any demographic, and studies show that both Millennials and Gen Z are willing to pay more for products by sustainable brands and that they are likely to make purchase decisions based on values and principles,” Brooks said. “In addition, how sustainable a company is will have an impact on labor issues. Research shows that 70% of Millennials prefer to work for companies with strong sustainability agendas, and there is every indication that Gen Z will embrace that same attitude. Moving into the future, the truth is that sustainability is not a trend but a necessity in business.”

The younger pet parent is continuing to fuel the humanization and premiumization of pet food. These pet parents are looking for products that mirror those that they feed the human members of their families.

“That humanization of pet food is alive and well in the business continues to drive consumer behavior — ‘If I’m eating a sous vide product, maybe I should try that for my pet,’” said Jason Robertson, vice president, food and beverage for CRB. “I think you’re finding consumer buying habits are mirroring their own.”

Shoppers looking for plant-based options for their own food purchases are looking for more plant-based options for their pets as well. This trend is forcing creativity in product innovation.

“The humanization of pet food has been trending for years and there are no signs of slowing down,” said Ernie Ambrose, director of Innovation at Champion Petfoods. “As more pet parents look to feed their pets like members of the family, variety and enjoyment during mealtimes will continue to drive growth across premium pet food. We’ll continue to see innovations in all segments, from dry food to meal toppers, to wet or freeze-dried food, to custom bowls and beyond.

“Additionally, more people are invested in their pet’s food than they are in their own food. The importance of longevity and vitality will become more prevalent in the premium space with quality ingredients offering the greatest benefit for consumers,” Ambrose added.

Ultimately, pet parents all want what’s best for their pets — top-tier nutrition that will keep their four-legged family members as healthy and happy as possible, for as long as possible. If new products featuring customized nutrition and premium health benefits are the answers, then the pet food consumer will continue to push the industry toward those innovations. And as the industry continues to grow and evolve, it will get closer to meeting that demand.

“I think that over time the industry will get closer and closer to meeting the needs of what consumers want from a trust perspective, from a transparency perspective, and from a customization perspective,” Kaufmann said.

Ruffolo added, “Customers are faced with an ever-changing array of choices with competing product claims from established brands and channels, as well as from new brands and new channels. Ultimately, the consumer will have the power to determine the winners (and losers) among these brands, retailers and channels, and force the market to adapt to this new reality.”