By Charlotte Atchley

May 2022

The push

and pull

Grains have long been the foundation of the American diet, but consumer behavior doesn’t always comport with nutrition science.

stock.adobe.com

Despite the prevalence of low-carb dieting over the past generation — a trend that keeps cycling back around with different names — grain-based foods have made up the bulk of people’s diet for the vast majority of human existence. Bread in various forms has served as the foundation of a meal and accounted for more calories consumed than any other food category. It’s only been since the 1970s and even more persistently since the late 1990s, that some people have truly shunned carbohydrates, and therefore, grain-based foods, to achieve what they believe to be a healthier lifestyle.

But consumer perception of what’s good for them and what’s not fails to line up with what scientists have discovered and what science continues to learn about the place grains and carbohydrates have in the diet. Even now, despite consumers’ renewed interest in baked goods, low-carb persists. In today’s iteration, the baking industry contends with the keto diet and demand for baked goods that deal in net carbs, or those carbohydrates which are digested and used for energy.

You might also enjoy:

Looking ahead, producers, processors and retailers must appeal to evolving demographics.

Argentina-based company has made major inroads with HB4 wheat in Argentina, has sights set on Australia and the US

The evolution of grains

The industrial revolution brought about many technological advancements, but the ability to mill flour on a larger scale made it possible to commercially produce bread. Previous to this advancement, most people baked their own bread with whole grain flour.

“These flours were milled and consumed on a shorter timeline and a smaller scale,” said Sarah Corwin, PhD, RD, senior principal scientist, plant-based, Ajinomoto Health & Nutrition, who studied carbohydrate chemistry and digestion at Purdue University. “By having large-scale refinement technology, we observed that the fat, B vitamins and proteins in whole grain spoiled the flour, so the shelf life was much shorter. This wasn’t a problem before because we were consuming it as it was produced, but now we’re able to create very large amounts of flour and baked goods way ahead of what we needed, so we needed to extend the shelf life of that flour.”

To do that, millers removed the bran and germ, extending the shelf life at the expense of the nutritional value. Most baked goods were then made with refined grain, but because grain-based foods made up the bulk of the American diet, it wasn’t long before nutrition deficiencies started showing up in the population.

To counteract that, the United States government began food fortification and enrichment programs: adding iodine on a voluntary basis to salt in 1924 and vitamin D to milk in 1933. In 1940, flour entered the spotlight with the Committee on Food and Nutrition recommending it be enriched with thiamin, niacin, riboflavin and iron. The US Food & Drug Administration established a standard of identity for enriched flour including these initial nutrients, and by 1942 much of the bread being produced in the US was meeting this standard voluntarily. In 1998, folic acid fortification was added to the standard of identity to address neural tube birth defects.

“It’s been documented since that time that the incidence of neural tube birth defects has fallen precipitously, and it’s directly related to that,” said Glenn Gaesser, PhD, professor, College of Health Solutions at Arizona State University, and member of the Grain Foods Foundation Scientific Advisory Board. “And you see that in countries that don’t have mandatory fortification you don’t see the same sort of benefits. It’s just one example, but it’s pretty clear cut.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that this addition has prevented neural tube birth defects in about 1,300 babies each year. These defects have decreased by 35% in the US since 1998.

While enrichment has certainly boosted the nutrition of refined flour — and complex carbohydrates offered by refined flour are also helpful to the human body — whole grains offer an elevated nutritional profile to consumers. While commercial baking may have been geared toward refined flour because of the ease of production and shelf life, the scientific community has been wise to the nutritional powerhouse that is whole grains for quite some time.

“In the mid-19th century, when nutrition science was only in its infancy, whole grains were a staple food in American health sanitariums,” said Kelly LeBlanc, MLA, RD, LDN, director of nutrition, Oldways. “In fact, many commercial whole grains today, such as graham flour and whole grain cereal, can be traced to the teachings of Sylvester Graham and John Harvey Kellogg, who were prominent and controversial health influencers of their time.”

Even at the turn of the century, Ms. LeBlanc pointed out that scientists noticed people eating brown rice in East Asia were significantly less likely to develop beriberi, a chronic disease that is potentially deadly, than their counterparts who were eating white rice.

“This finding paved the way for the discovery of vitamins and helped shape our understanding of the nutritional value that whole grains have to offer,” she explained. “Over the years, as nutrition scientists learned more about the importance of micronutrients like vitamins and minerals, as well as other essential nutrients like fiber, it became increasingly clear that whole grains were an important part of a nutritious diet.”

The taste of healthy

Despite the profound knowledge, even among fickle consumers, that whole grains are a benefit to the body, consumption of whole grains has always been slow. Taste remains the No. 1 reason consumers make repeat food purchases, regardless of any virtue-signaling they may provide their friends, family and market researchers. And for many, products made with enriched flour simply taste better.

“It’s been a real challenge to get people to consume more whole grain foods,” Dr. Gaesser said. “And it’s not from lack of advertising or general knowledge that whole grains are good. You can find that easily on the internet. There are all sorts of studies and websites that tout the health of whole grains. You can look at the scientific literature and see that whole grains are associated with lower risk of a lot of chronic diseases, so why people don’t consume more I think it’s just a matter of taste, texture and maybe even color.”

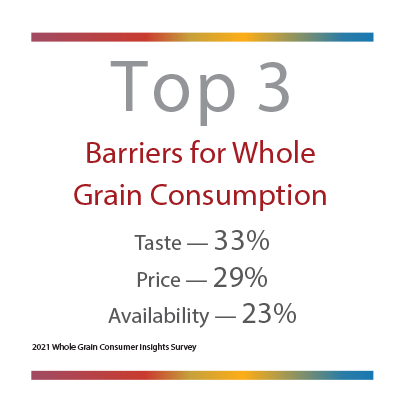

The 2021 Whole Grain Consumer Insights Survey found that the biggest barriers to whole grain consumption are taste (33%), cost (29%) and availability (23%). Things may be changing, however, as consumers have become more educated, and millers have created whole grain flours that create more palatable breads packed with nutrition.

That same consumer insights survey also found that more than a quarter of respondents reported there is nothing keeping them from eating more whole grains, and more consumers reported that they see the taste of whole grains as a benefit rather than a barrier.

“Zooming out a little further, lack of exposure to whole grains had also been a barrier to whole grain consumption, but this is an area where we’re really seeing progress,” Ms. LeBlanc explained. “Feeding experts note that food preferences are not set in stone, and that in order to enjoy a food, we really need repeated exposures to it over time.”

The Dietary Guidelines of Americans quantifying whole grain recommendations influenced school lunch programs and the bakery products that could be offered to schoolchildren. The baking industry has used more finely milled whole grain flours and a combination of whole grain and enriched flours to create soft and smooth products for school lunch programs and even the retail shelf to satisfy even the pickiest of eaters.

“Thankfully, today’s bread makers have a better understanding that whole wheat flour cannot simply be substituted 1:1 for all-purpose flour, and that different varieties of wheat are well-suited for different end products,” Ms. LeBlanc explained. “By experimenting with different types of whole grain flours, milling to a smaller particle size, increasing hydration of the doughs and investing in product research and development, today’s bakers and manufacturers are able to offer more delicious whole grain breads than ever before.”

Just last year, Bimbo Bakeries USA (BBU), Horsham, Pa., launched Soft & Smooth wheat bread under its Sara Lee Delightful line. The Delightful line contains no added sugars and contains only 45 calories per slice in addition to this variety delivering whole grain nutrition with a soft and smooth texture. In January 2021, the company also introduced Sara Lee Delightful White Made with Whole Grain, which also claims to be keto-friendly with only 6 grams of net carbs per slice.

Flowers Foods, Thomasville, Ga., also touts a wide variety of whole wheat and whole grain breads with a soft and smooth texture, and some formulated with honey.

New products that provide a range of textures and flavors associated with whole grains have helped Americans learn to appreciate the flavor and texture the grains contribute to baked goods.

“In fact, in 2010, whole grain bread sales began to surpass those of white bread,” Ms. LeBlanc pointed out. “Today, whole grain breads are a trendy staple at artisan bakeries across the country, and whole grains like quinoa, farro and brown rice appear on fine dining menus and fast casual alike. Additionally, locally grown whole grains provide a unique path for bakers and food producers to connect with the Earth and support local food systems and economies.”

For consumers who are interested in the taste and texture of whole grains, there’s a wide array of options to choose from, whether it’s BBU’s Oroweat brand or Flowers Foods’ Dave’s Killer Bread, which both market to a health-conscious and socially conscious consumer.

“There are so many options that it would be almost impossible that someone couldn’t find something that was palatable,” Dr. Gaesser said. “In the past, some of the whole grain breads just tasted like cardboard, but today, the coarse texture can be minimized, and that’s paved the way for all the options we have now.”

The consumer conundrum

While the science around the benefits of whole grains and enriched grains is clear and consistent, the movement toward low-carbohydrate diets has persisted in the collective consumer conscious since the 1960s. Carbohydrates gained a brief respite in the 1980s while fat took a turn at vilification, but in the 1990s, the spotlight turned back toward carbohydrates and simple sugars. Dr. Corwin attributes this persistent vilification with the growing understanding of macronutrients.

“As the science progressed, we started to understand the caloric distribution of macronutrients,” she said. “That’s when we began to understand that fat is higher in calories than protein, so maybe we should cut down on fat and carbohydrates. Then sugar became the next target because it’s a simple carbohydrate. This also coincided with the observation that with a ketogenic diet, glycogen stored in muscle (which is more than 10 times its weight in water) is lost, resulting in the number on the scale going down. It’s been a long progression of carbohydrates being viewed negatively, even though grains are the main source of carbohydrates in the American diet.”

Dr. Gaesser also pointed to the fixation on dieting and the growing rates of obesity in America. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2013-2016, found that 49.1% of US adults tried to lose weight in the past 12 months, while nearly 40% were considered obese. Among the adults who tried to lose weight, exercise and eating less were tied for the top spot with 62.9% of respondents reporting these strategies.

“When you look at diet from the standpoint of how to lose weight, you see a smorgasbord of diets that have vilified carbs, whether it’s low-carb, keto or paleo,” Dr. Gaesser said. “Carbohydrates are the most commonly consumed macronutrient, so for most of the last century, about half the calorie intake for the average American comes from carbs. So if you want to lose weight, you need to cut calories.

Carbohydrates are an easy target. It makes sense from this perspective to cut out something that you’re consuming a lot of. However, research shows that in terms of weight loss, it’s the calories not the carbs.”

Dr. Gaesser also pointed to the biology of how carbohydrates are stored in the body as to why people find so much initial success with cutting carbohydrates.

“For every gram of carbohydrate you store in your body, you store almost 3 grams of water with it,” he explained. “So if you lose the carbohydrate, you also lose the water weight. When people go on a carb-free diet, they can drop 5 to 10 lbs within the first week, and they think this is the best diet ever because they’ve never experienced that. The low-carb diet gurus have capitalized on that phenomenon.”

It’s these stories about quick weight loss, Dr. Corwin said, that attract the public more than the science because stories can be so powerful.

“But anecdotes aren’t scientific evidence,” she said. “MSG is a really good example. One person published one article saying they had a headache and a stomachache after eating Chinese food. And that resonated with someone else, and they repeated it over and over again. MSG is also naturally occurring in Italian food in the Parmesan cheese, so why is this phenomenon so specific to Chinese food? Only recently in the last four years has it really come to light that the reason why people thought MSG was bad was xenophobia and a couple of misinformed articles in the 1960s.”

Today, the sexy diet people are hopping on board is the ketogenic diet, which on its own has a long, well-documented history to treat epilepsy. But it has reached the mainstream consumer who may not need this extremely restricted diet to treat anything but a waistline. Dr. Gaesser pointed out that there could be unintended consequences for those who cut carbs without a medical reason to do so, whether that’s epilepsy or celiac disease. Two research papers published in major journals he cited show an association between cutting out gluten and increased risk of diabetes and heart disease.

“If you cut out wheat — Americans’ major source of gluten — you’re cutting out a major source of fiber,” he pointed out. “Studies show that dietary fiber — particularly cereal fiber — is inversely associated with diabetes and heart disease.”

There’s been chatter about the healthfulness of sprouted grains, low-carb breads and long fermentation products like sourdough, but the science is leading to fiber.

“There is really interesting research starting to hit publications around what type of fiber is beneficial, but there is no real research around some other consumer trends,” Dr. Corwin said. “Despite minimal research backing the lasting benefits of probiotics, some research supports prebiotics and fiber for gut health. I believe prebiotics and fiber are the future of gut health. If science drives trends, then the next steps will be determining what those types of fiber are. Hopefully, that’s how we’ll be developing new products.”