By Charlotte Atchley

August 2021

Leading the

Pack

Whether increasing production line capacity or reducing plastic waste, sealing in freshness remains at the heart of packaging.

Packaging does so much for a bakery or snack product. First and foremost, it protects it, and ideally prolongs shelf life so that consumers can enjoy a baked good or snack at its peak quality. But packaging also can communicate to consumers about a brand and provide new ways for them to enjoy the product, whether for the convenience of a more mobile lifestyle or variety packs for family members with different tastes.

“We ask packaging to do a lot of things: promote the product, protect, transport, provide information of the product,” said Tom Egan, vice president, industry services, PMMI. “You want to know what’s in the product, whether that’s calories or potential allergens. Packaging provides all of that.”

Many packaging innovations of the past 100 years have arrived to meet those needs, whether that’s increasing throughput on production lines, extending shelf life or delivering the information consumers want. And packaging innovation continues to meet the food industry’s needs for the future.

A need for speed

The first patent for a pre-fabricated carton was issued in 1879 to Robert Gair, and it would be used by Nabisco in 1896 to package the company’s crackers. In 1906, Kellogg Company, Battle Creek, Mich., used the cardboard box to store its Toasted Corn Flakes, implementing a packaging design that hasn’t really changed in more than 100 years. In some ways, if it’s not broken, don’t fix it.

Just because the carton worked so well doesn’t mean companies stopped innovating. On the contrary, the packaging industry has seen leaps in innovation, particularly automation, that has enabled exponential growth for the baking and snack industry.

“You need automation in order to mass produce not only the product but also the package,” Mr. Egan said. “So automation, the machines themselves even before we get to electronic automation, is what really is driving the growth of baking and snack.”

Form/fill/seal technology empowered bakers and snack manufacturers to package product at an accelerated rate. The vertical FFS machine was patented by Walter Zwoyer in 1936. Mr. Zwoyer worked at a candy factory and was looking for a way to quickly package individual candies when he developed the machine.

“When you can package products at a higher rate on VFFS, all the rest of the equipment has to run at a faster rate,” Mr. Egan explained. “Allowing multiple lanes to be formed at once improves throughput and expands the market opportunities.”

Robotics promise the next leap when it comes to increasing production and streamlining the packaging department. While the first packaging robots were deployed in the 1960s and ’70s, they have taken some time to catch on. Schubert’s Robby the Robot demonstration at a trade show in the 1970s showed the industry the potential of robotics in the packaging department.

“What Schubert did in the confectionery market was demonstrate the ability to do a higher speed of a combination pack whether it’s the solid chocolate or combination of solid and filled chocolate,” Mr. Egan explained. “That allowed the industry to expand and increase the number of SKUs it was producing.”

By automating the packaging department, bakers and snack manufacturers were able to make their production floors more flexible and offer more products, packaged in different formats.

Keeping it fresh

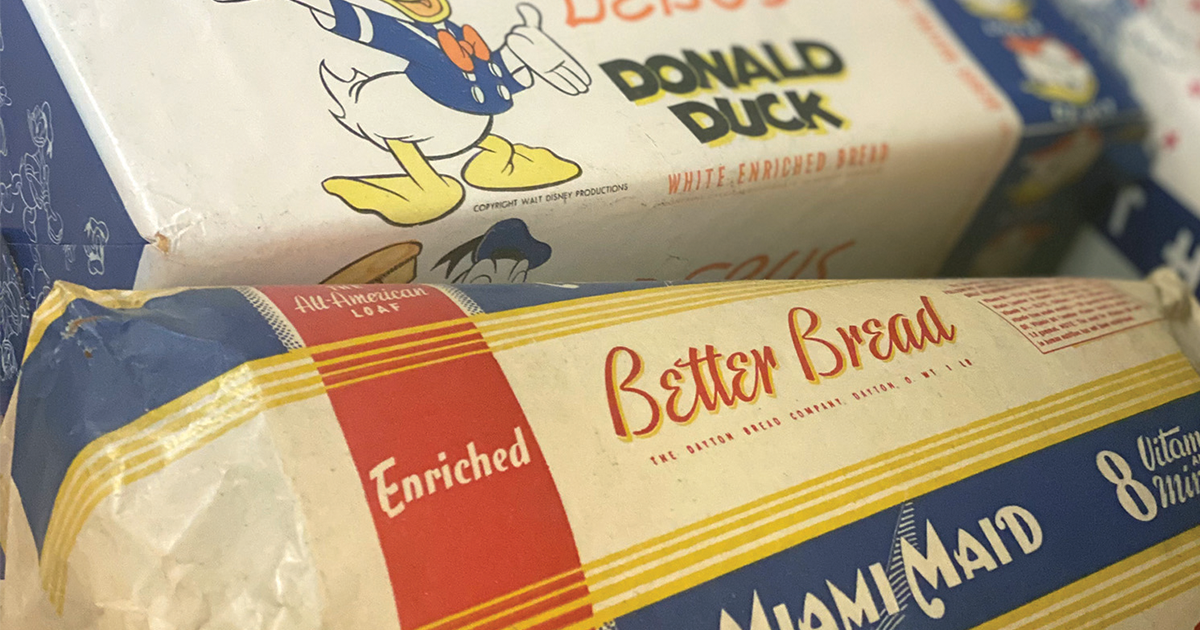

And then there’s sliced bread and the bread bag itself. The original bread slicer dates back to 1928 and was developed by Frederick Rohwedder and perfected by Gustav Papendick, who added the capability to wrap the bread in wax paper and package it in cardboard trays. In 1930, Wonder brought sliced bread to the entire nation, which continues to be a colloquial measure of innovation … “the greatest thing since sliced bread.”

The convenience of sliced bread was a hit, but keeping sliced bread from going stale too quickly was a challenge and required packaging that preserved its softness. From wax paper to cellophane to polyethylene, materials have evolved to keep bread fresh even sliced. The 1960s brought plastic technology and bread bagging technology to automatically package bread in its now universal packaging format, a polyethylene bag with a twist tie or clip.

“If it weren’t for certain plastic bags, we wouldn’t have been able to have a 7-day shelf life for bread instead of a 2-day shelf life,” said Brian Wagner, co-founder and principal at PTIS, LLC.

According to Tom Dunn, managing director, Flexpacknology, efficient bread bag packaging required a coordinated effort of several needs. The industry had to develop the side-weld bag making process for printed polyethylene film and implement a wicketing method to stack bags for transport to the bakery. For the actual bagging process, machines had to remove bags from those wickets, open them with a puff of air and push a loaf of bread inside before applying a closure. All of this came to fruition in the 1960s when Alvin Formo developed an automatic poly bagging machine that was then tweaked after acquiring the patent rights to a bread bagging machine developed by Roy Willard and Bill Noyes.

While FFS machines and bread baggers may have met the needs of preserving shelf life and speeding up production, the stand-up pouch, introduced in the ’60s, also brought new form and the ability for resealability to snack and bakery products. The stand-up pouch opened up the possibility of packaging beyond the carton.

“The pouch allows flexibility to not only display the product in a whole different way at endcaps and points of purchase, but it also allows the convenience to carry it,” Mr. Egan explained. “When you consume half the contents, the pouch collapses and takes up less space. It can be squeezed and fit into spaces a rigid container can’t.”

Modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) offers the potential to be the next frontier when it comes to keeping food fresher for longer. This technology replaces the oxygen inside a bag, like a bread bag, with a gas mixture that will stave off staling. It originated in the UK and Denmark in the 1970s and continues to gain application across the food industry. In the 1990s, Mr. Wagner worked with the United States military to use MAP to extend the shelf life of bread and cake products delivered to soldiers in the field.

“We developed a MAP extended shelf life technology that really required just removing the oxygen so mold couldn’t grow and doing some formulation work so staling couldn’t happen,” he said. “In the early ’90s, we developed a three-year shelf life bread and cake item, which is super relevant for soldiers who hadn’t been able to have bread and cake in the field until that time.”

All about the consumer

While packaging may have started out as an answer to staling and molding food, ultimately, Mr. Wagner said, it’s about serving a consumer need, whether improving soldier morale or delivering a satisfying treat.

“The consumer is No. 1 because if it doesn’t taste good, and it doesn’t deliver on brand promise, the consumer isn’t going to buy it,” Mr. Wagner said. “Packaging plays a huge role in the consumer mind in the bakery world.”

Packaging communicates a lot to the consumer. Whether it’s the brand design and colors on the packaging or the nutrition and ingredients listed on the packaging, consumers turn to packaging to tell them a lot about the product they are looking to purchase. While eye-catching graphics, a brand story and nutritional information are obvious elements to communicate with packaging, even packaging integrity is critical to tell consumers something about the safety and freshness about what is inside.

“We had an issue with frozen desserts where the cartons were getting crushed at retail and the perception that gave consumers about the brand and how that would impact consumer trust,” Mr. Wagner said.

A secured, sturdy package communicates to consumers that the product inside is protected and fresh. A resealable and tamper-evident closure states that they can trust what’s inside is safe to eat and will stay fresh longer. Mr. Dunn pointed out that longer supply chains, bakery and snack manufacturer consolidation and retail labor costs have also all spurred packaging innovation.

“Sturdy plastic trays overwrapped with barrier films replaced paper ‘dump bags’ and paperboard cartons for baked cookies as shock and vibration forces during transportation increased,” he explained.

Universal Product Codes (UPCs) in 1973 standardized product identification and tracking and leveled the playing field for products in front of the consumer.

“The printed UPC on snack and bakery packages gave powerful customer loyalty opportunities to merchandisers at the expense of consumer goods brand equity,” Mr. Dunn explained. “As a result, store brands now compete effectively with national brands.”

You might also enjoy:

Overcoming obstacles and chasing innovation, the pet food industry prepares for its promising future.

Today’s meat and poultry processors carefully manage expectations to feed people, preserve the planet and deliver profits in the future.

Packaging of the future

Packaging has come a long way from the tried-and-true carton and the wax paper bread wrapper. Machines and materials have pushed the limits of automated production and extended shelf life of products and made food more convenient for people to eat and store.

Extended shelf life, increased throughput, greater flexibility and added convenience will always be at the forefront of packaging needs, but today’s challenges have evolved to other consumers.

Sustainability is at the forefront with plastic being public enemy No. 1 in some cases. As populations grow, resources dwindle and consumers become more concerned with waste. More consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies than ever are making commitments to seek out packaging made with recycled or other materials that are less harmful to the environment. The Consumer Brands Association (CBA) reports that the 25 largest CPG companies have all made commitments to minimize packaging or reuse materials, and 80% of those companies have set goals of using fully recyclable packaging by 2030.

“There is going to be a billion more people on this planet, and we won’t have the resources,” Mr. Wagner said. “That’s been driving innovation around materials. How do we use less plastic, different plastics or design packaging so it can be reused?”

Before the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, sustainability was a top concern for consumers, especially when it came to packaging. According to a consumer study by CBA, this is still true, although there is some more nuance. Eighty-two percent of Americans said they were concerned with the environment in 2020, down from 90% the year before, and 80% said they are concerned about single-use plastics compared with 87% in 2019. Consumers seem to understand that plastic has its place — especially in keeping food safe in a pandemic. CBA’s study found that 50% of Americans said recycling became even more important during the pandemic to handle the increase in single-use plastic and packaging, while 45% said it was equally as important as before.

Packaging made from recyclable materials, lighter gauge materials, bioplastics derived from plants and chemical recycling technologies are all on the table for sustainability, and new technology is constantly being developed to pursue those goals.

While the pandemic may have brought nuance to the sustainable packaging need, it jumpstarted e-commerce and how omnichannel will influence the packaging of the future. This growing channel has changed the supply chain but also increased consumer expectations of convenience and product quality.

“You’re buying something online, and you want it to arrive exactly the same way that resulted from the traditional packaging and supply chain process, but the number of touchpoints and handling could change significantly,” Mr. Egan explained. “The number of times the package is handled goes up, and the package still needs to protect the product.”

Resolving that issue is driving much of packaging innovation happening today.

“There are so many companies trying to figure out how to extend the shelf life of any product to meet the needs of e-commerce,” Mr. Wagner said. “Like shipping a hamburger to your house and packaging it so it will still be fresh. Any way you do it, even insulated packaging for frozen goods, it’s going to be expensive, but there is a lot of innovation going on because it’s a huge market need.”

The digitalization of manufacturing will also influence future innovations of packaging. Invisible codes on packaging will be able to deliver more information to consumers as well as send data back to manufacturers. Production lines are becoming more integrated, delivering production data to operators in real time.

“Digital transformation is causing us to rethink the way we do everything,” Mr. Wagner said. “You can monitor packaging uptime and downtime and make immediate changes instead of waiting a week when you’re reviewing your data. All of these possibilities are getting less expensive, and we will be able to use them in so many new ways that will drive value and take waste out of the system.”

Some innovations over the past 100 years have been industry-changing events, but Mr. Egan pointed out that packaging is always improving even if in small ways.

“There are constant incremental improvements being made all the time,” he said. “The industry is always looking for ways we can do better. We still need packaging that will protect, promote and improve the point of use at the consumer level.”

Change, incremental or revolutionary, for packaging is on the horizon.