By Joel Crews

October 2022

Automation

Mission

The evolution of meat processing in the future depends less on humans and more on technology

Georgia Tech Research Institute

laughtering and processing facilities where meat and poultry are manufactured have improved dramatically over the past 100-plus years. Comparing the abhorrent treatment of livestock and the people working in the plants in the early 20th century, as chronicled in Upton Sinclair’s 1906 infamous novel, The Jungle, to the operations of today’s processing plants demonstrates how innovative solutions and a commitment to continuous improvement by industry stakeholders have made game-changing improvements. Along with addressing the well-being of livestock and plant workers by vastly improving working conditions, the industry’s supply chain infrastructure has evolved significantly since Sinclair’s portrayal of the stockyards of Chicago, which also resulted in food-safety advances, improved food quality and efficient production at processing plants that operate using sophisticated technology, and increasingly, automation.

Industry thought leaders unanimously agree the processing plants of the future will include even more technology and refinements with goals of improving operational efficiency, increasing yields, minimizing the impact on the environment, and addressing a labor shortage that has hamstrung the industry for years.

Monitoring and analyzing operations based on cloud-based data collected from facilities is already being utilized by meat and poultry processors to streamline production and artificial intelligence technology applied at plants is proving beneficial in predicting and forecasting maintenance issues and identifying opportunities for operational improvements.

Making the leap

The industry’s biggest processors have done more than just dabble in innovations that were recently thought to be technology pipe dreams and most have committed resources to continue developing even more futuristic solutions for the next generation of meat and poultry processing plants. A focus on automation is a common theme among them.

For example, within the past decade São Paulo, Brazil-based JBS S.A. embarked on learning more about how it could apply machine learning at its 300-plus processing facilities. In 2015, JBS made a multi-million-dollar investment to own a controlling share of New Zealand-based Scott Technology. This year, JBS Foods Canada announced it was investing $71 million in a project with Scott Technology to make its Brooks, Alberta, warehouse fully automated.

“This new system will help reduce storage costs and errors and deliver improved inventory turns, while also improving worker safety as one box can weigh up to 110 lbs,” said John Kippenberger, chief executive officer of Scott Technology, when the project was announced in July. “It represents significant efficiencies and cost savings for JBS Foods Canada and will be the largest project of its kind for Scott to date.”

Late this past year, during a presentation at an investor meeting, Hormel Foods Corp.’s group vice president of supply chain, Mark Coffey, said the company routinely earmarks millions for automation in each year’s budget.

“With the uncertainty of labor and this tight labor supply, we are ramping up our investments in automation,” he said.

Earlier this year, Springdale, Ark.-based Tyson Foods Inc. announced it had 12 new plants under construction in the United States, with automation playing a critical role in all of them. At the beginning of its 2022 fiscal year, the company said it budgeted approximately $1.9 billion to invest in additional capacity and automation.

One of those projects is Tyson’s bacon processing plant, a $355 million, 400,000-square-foot project underway in Bowling Green, Ky. Gregg Uecker, Tyson’s senior vice president of operations of Prepared Foods is leading the project in terms of construction, design and equipment. And automation is a big part of the plant’s operation, which is scheduled to start up in late 2023. He said projects of this scale have to be built with a future-first mindset.

“We aren’t designing the plant for today and today’s processes and today’s problems,” he said. “We’re designing a plant so that 15 and 20 years from now it is still viable and still highly competitive.

“So, you have to think way differently. Where’s the world going to be? How do I not plan myself into a corner? How can I think about looking at technology?” he said, adding that there is a balancing act between building for the future and ensuring reliability when it comes time to execute production. “When it comes time to press the green button and start the plant, it’s got to make bacon,” he said.

He said the bacon plant is an example of how new plants address today’s issues while accounting for what might be tomorrow, which depends on the future-minded approach of the project leaders. Automation is an important part of the future, but so is an operations strategy, which is data based.

“We need to look at staffing and availability of labor, the cost of labor, but also making jobs easier, more precise and really allowing control systems to run them versus people running processes,” Uecker said. “Automation is a way of life. It’s not a project anymore. It’s kind of like it’s just part of how we work.

“And I think about data the same way. We have to collect more data from the processes. We have to get more insight from these processes with more sensors and more controls on anything that we do today than we ever did five years ago, 10 years ago, and now we have to make better decisions to reduce variability and increase the speed of business with that data.”

Poultry focused

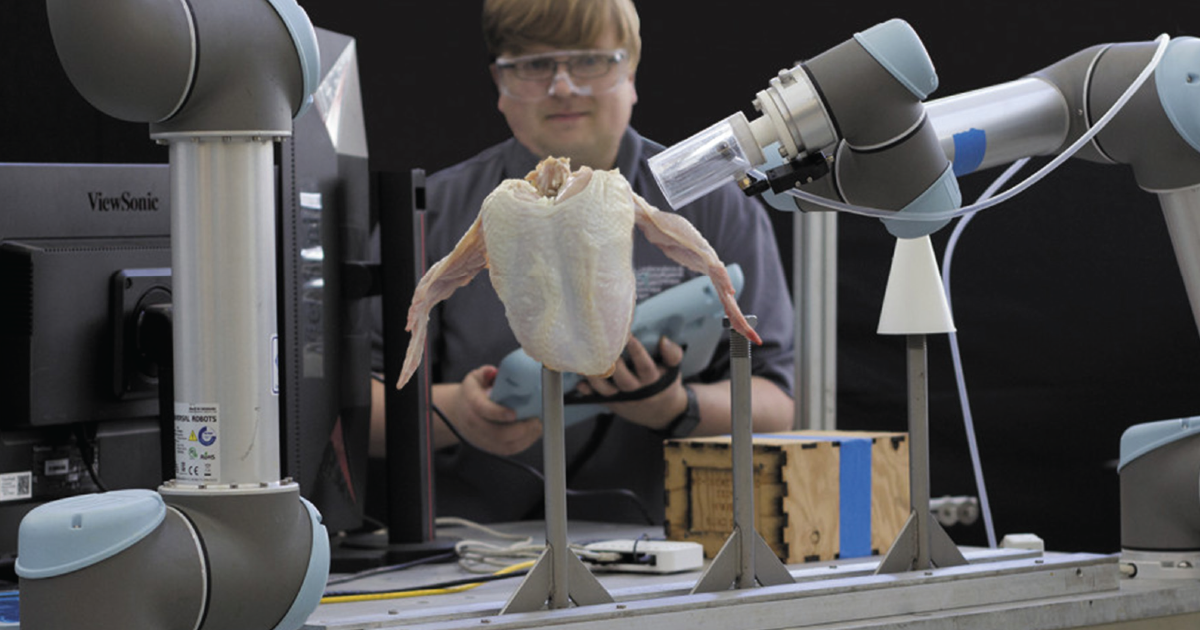

Konrad Ahlin, PhD, Georgia Tech Research Institute, Aerospace, Transportation & Advanced Systems Laboratory, believes the time for widescale utilization of automation and robotics in the poultry industry is now. And he said once a foothold is established, the future is bright.

Ahlin, who is a relative newcomer to the food industry but an established expert when it comes to automation and robotics, is quick to point out the unique challenges that are inherent in applying robotics in meat processing applications, however.

“I see food manufacturing as the next big frontier for robotics. Because if you look at a lot of the factory manufacturing and areas where robotics are typically used, including assembly lines, often the robot’s job is set pre-planned ahead of time.”

But when the focus is on a product that is variable in size, texture and shape, “it’s a very challenging problem for robotics. And that’s one of the things that really got me interested in the field. As a roboticist, how are we going to advance robotics to face the incoming challenges of food manufacturing?” Ahlin said, not the least of which is the labor shortage.

Two-arm advantage

He said that in traditional manufacturing applications it is common to see one robot arm designed for a singular task. These arms are typically large and operated in areas that are inaccessible to humans because of their size and weight and the danger they can pose to people. And while there might be multiple arms positioned close together, they are not designed to interact with each other to perform tasks. However, the concept of a “cobot,” a collaborative robot, has become more popular for manufacturing applications because they are usually less bulky and heavy and are less dangerous than their single-arm counterparts.

“The modern, interpretation of a “cobot” is a six- or seven-degree freedom robot arm, that is made to be operated within a human workspace if it has built-in safety precautions and is less bulky and heavy,” Ahlin said. “While less powerful, it wouldn’t be desirable for it to run into people or things, it also wouldn’t be catastrophic if it were to do so. What that allows for now is instead of just a robot arm, interacting within a human’s workspace, you could have multiple robot arms interacting within a shared workspace.”

For poultry processing applications, one area of research showing promise utilizes two interacting robotic arms to rehang chicken carcasses, which has obvious benefits in terms of labor savings and efficiency. This type of “cobot” application takes advantage of pairing a human to be the decision maker in the process with a robot that specializes in the manual labor task.

“So, is there a way to marry the manual labor of the robot with the decision making of a person? And our answer for that is to have this shared collaborative environment within the virtual world where the human and the robot can share information very naturally, and the person can then direct the robot and tell it where to pick up a bird using the suction gripper,” Ahlin said.

One of the benefits of this concept that has been proven in the lab is that the task can be completed remotely, with the human-based decision-making being done in one location to direct the robotic arm to hang a chicken carcass on a cone like those used in a poultry plant cut-up line.

“You don’t need to be in the same physical location, you just need to have an internet connection,” Ahlin said.

However, utilizing this technology is still in the research phase and likely years away from widespread implementation in plants. In the meantime, Ahlin is confident that progress will be made.

“I am very optimistic that in 10 years, the poultry processing in particular will look vastly different than it does today in terms of how much automation will take place,” he said.

“I don’t think the poultry industry needs to advance to some mythical level to be good enough for robotics,” Ahlin said. “I very much feel that robotics needs to advance to meet the challenges seen within the poultry industry. And robotics just recently has gotten to a level where it can start to address those challenges.”

Red meat and robots

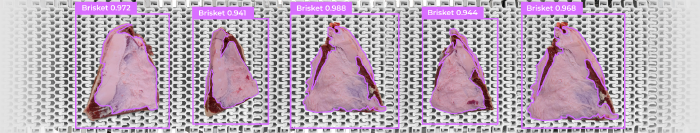

When it comes to meat processing and automation, Chafik Barbar, chief executive officer of Marble Technologies, has gone all-in on the opportunities. He founded the Cambridge, Mass.-based company at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic after realizing the potential solutions automation hardware and software could deliver to the country’s plants that were reeling from the backlash of the virus. His company was founded on the basis that most processors are forced to operate with about 20% fewer workers than they need. Marble creates the software ‘brains’ for hardware to automate processing tasks using artificial intelligence to deliver automated solutions that can adapt to the variation in beef and pork products.

Growing up in Nebraska and a graduate of the University of Nebraska, Barbar has a background in agriculture and food technology. As a software developer, he co-founded GrainBridge in 2009, an Omaha-based start-up that provided financial risk management for crop and livestock producers. That company was acquired by ADM and Cargill in about 2018. He then moved to Massachusetts and earned an MBA from MIT Sloan School of Management and was determined to get back into food technology again, despite graduating during the pandemic.

He soon learned that one of the biggest post-COVID pain points in the meat industry was the labor shortage and began building a team of professionals who understand meat processing with technology experts that solved similar challenges in other industries.

“I’m trying to mash up meat science with other disciplines,” Barbar said.

He said that while many in the industry would criticize it for being slow to adopt automation, the argument could be made that there is an advantage to being a late bloomer. All eyes, it seems, are on the meat industry, due in part to COVID-19, consumer interest in food sourcing and global initiatives related to animal welfare, sustainability and consolidation concerns. Barbar added that the time is right for automation in the meat industry. He said the technology has been proven in other industries and is not only more affordable than in years past, but it is also evolving to address the variability issues inherent in automating meat-processing using more sophisticated learning software and artificial intelligence. He also pointed out that the labor pool for jobs in automation is attracting more candidates to the food industry from other industries given the level of software and hardware development and engineering skills required.

He said the need for solutions in this segment is understood by engineers and they aren’t deterred by working in what was once considered a less-than-glamourous industry.

“People understand what this is; they really get it and I’m not having to explain the problem I’m solving,” he said.

He added that fortunately for automation companies like Marble, the industry’s largest players have budgeted tens of millions of dollars each year that are earmarked specifically for these solutions. Funds for enhancing and growing plant operations are also available in the form of government grants while venture capital in agri-food tech has more than quadrupled in the past five years, fueling the momentum to back any type of solutions that address supply chain problems.

He said all the factors are lining up to make this a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to address a longtime challenge in the industry and to boost it forward by 20 years.

“Ten years from now, I want people to look at the meat industry and talk about it as an example of automation,” Barbar said.

The most obvious solutions automation offers processors, for example in the pack-off area of a meat plant is in reducing head counts but not eliminating humans from the equation altogether. Instead, Barbar is offering processors human-in-the-loop automation and going from 20 to 30 people in a product sorting area of a primary beef processing operation, for example, and reducing it to four people.

He pointed out that those four people play a crucial role in the process because they serve as quality assurance workers who are the last line of defense to give products a final look before boxing and shipping. There is still much more to the processes than just flipping a switch and walking away.

“We’re still a long time away from this technology being lights out,” Barbar said.

He said the human factor is a necessary evil in the meat processing industry, unlike the automotive industry. Because no two carcasses are alike, dealing with consistency can be an automation hiccup, but software and visioning systems are available to deal with product variability.

“Where it gets real hard with variability is not the variability of the product, it’s the variability of the process. What happens on the fabrication floor is one chaotic process. It’s my argument that it’s man-made chaos. It’s not, God-made chaos. That is something we can fix long term but not Day One.”

He said real-world applications might target one process, such as trimming on a chuck line station and either making it completely automated without humans or use technology to make the first four trimming cuts and then conveying that to a single person at the end of the line to make the final cut or two to ensure it looks correct.

“I just saved the human four swipes with a knife,” Barbar said, “but we’re still pretty far from making automation work as well as humans. Humans are just phenomenal.”

While many meat companies have converted their inventory system and order pulling processes to a light’s out, human-free operation, that level of automation can’t be expected on the fabrication side.

Barbar said when it comes to opportunities for complete automation, “You see bits and pieces; you see robots here and there in pork, but still to a large degree, it’s pretty fragmented. You see automation kind of being sprinkled all over the place, but there’s just not these complete solutions that are mature enough to go in and solve for the reality of how these plants work.”

Barbar said the most opportunities are in retrofitting automation solutions for existing plants.

“That’s where the pain is,” he said. “I can sit here and design for new facilities, but I wouldn’t really be moving the needle for the industry.”

Marble’s solutions for today address the packaging area and the pack-off operations.

“I’m going after the end of the process; I’m going to the front of the process. It’s just my best approach to how do you tackle this beast.”

You might also enjoy:

Overcoming obstacles and chasing innovation, the pet food industry prepares for its promising future.

Today’s meat and poultry processors carefully manage expectations to feed people, preserve the planet and deliver profits in the future.