By Bob Sims

December 2022

Tomorrow's

Consumer

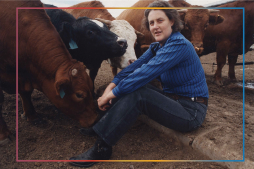

Looking ahead, producers, processors and retailers must appeal to evolving demographics

Antonio Diaz – stock.adobe.com

The COVID-19 pandemic makes it difficult to examine or analyze consumer trends in meat consumption and the role of meat in consumer diets over the last two to three years. The pandemic and supply chain issues during the pandemic, and those that followed and still linger, skew any short-term data available. Consumers, retailers, restaurants and all involved in the supply chain from farm to table face issues not seen in recent decades. However, data, analytics and insights provide a glimpse into how consumers shopped for, and ate, meat and poultry products during that time.

Meat motivation

In a sample size of 3,822 consumers, 210 Analytics LLC’s 2022 “The Power of Meat” report found the dominant driver for meat purchase decisions was a combination of product quality/appearance (60%), price per pound (48%) and total package price (39%). The next two factors were nutritional content (25%) and attribute claims such as organic, grass-fed, no antibiotics etc., at 23%.

Anne-Marie Roerink, principal at 210 Analytics, said that while consumers sometimes focus on the above average growth/trending areas of meat and poultry, such as those that emphasize attribute and better for you claims, etc., the large scale, traditionally raised meat and poultry products are the majority of sales. In most supermarkets, club stores and supercenters at least 90% of sales are of conventionally produced and processed meat and poultry.

“For those who emphasize sustainability, it is great to see that stores also have a growing availability of items such as organic, grass fed, and humanely raised,” Roerink said. “However, there is a danger in consumers believing that only those items address their areas of concern relative to better for them, better for the animal, better for the planet, and better for the community and workers. I believe it is important for us not to demonize conventionally raised meat but instead provide as many answers and transparency as to why all meat and poultry is nutritious, delicious, and humanely and sustainably raised.”

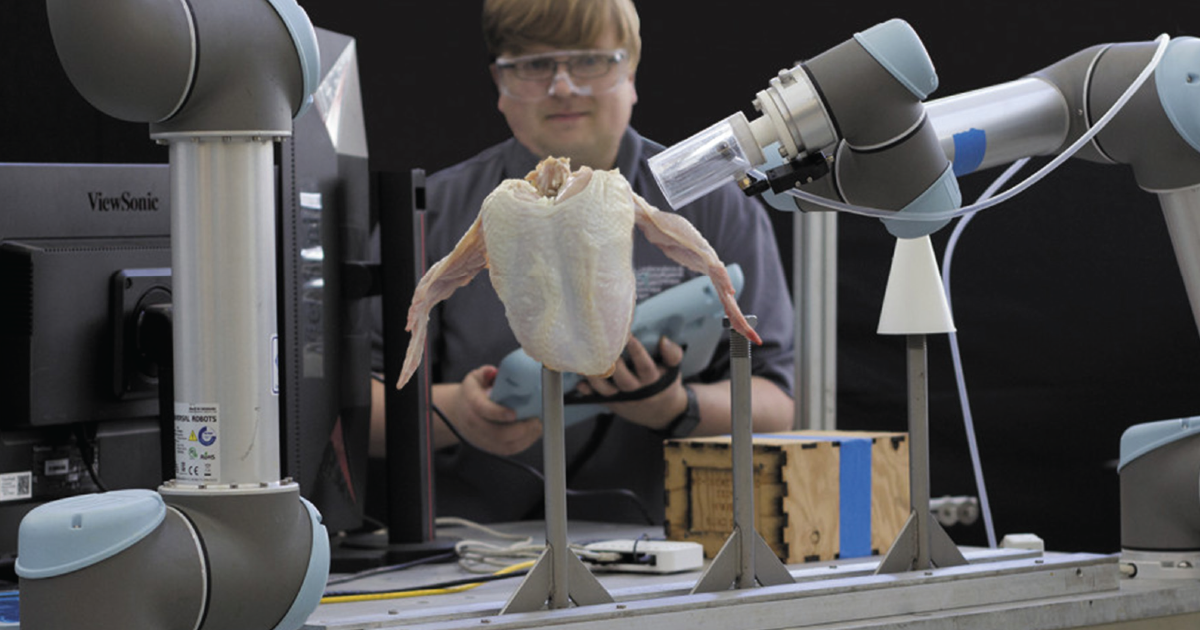

In addition, large-scale production and processing will likely remain a necessity as the global population continues to rapidly increase. In order to meet the increased consumer demand for meat and poultry, as well as the demand for transparency, technology will need to play a large role in conventional production.

“Consumers want transparency, traceability and to know the steak or chicken breast on their plate was sustainably raised,” said Steve Hixon, vice president of customer engagement, Midan Marketing. “You will likely see fewer human hands and more automation and analytic devices on the farm and in the production facility. The integration of a secure system monitoring in real time live animal health and gain, impact on land use and land regeneration will continue to develop.”

Today and tomorrow

Although no one has a crystal ball, some things happening today can be projected into the future. The entire grocery store, including meat and poultry, is seeing higher than average inflation. Retailers have begun to experiment with different unit sizes and in recent months there has been a shift to smaller packages.

“It is important for the industry to consider where the win nets out,” Roerink said. “Providing smaller unit sizes entails a risk for the department to lose some money toward a smaller purchase, but at the same time packages that are priced too highly may take certain consumers out of the purchase altogether.”

Another issue to deal with in the future affecting all forms of meat and poultry production and processing, and humankind, is the ever-growing population. The United Nations’ Department of Economic and Social Affairs projects the world’s population to reach 9.8 billion by 2050.

“Global population is another factor that will have an impact,” Hixon said. “As the world population grows to nine billion by 2050, the industry will need to continue to develop efficiencies related to production and logistics.”

With the transparency/sustainability/label attribute, etc., mindset of consumers growing out of a trend and becoming a mainstream attitude, there is no doubt it will affect consumer purchases into the future. Alternative proteins have gained a foothold in the market around this, as well as being an option to feed the growing population, and are on the mind of all in the meat industry, both within the alternative sector and the conventional and specialty animal protein sector. While both specialty animal proteins and alternative proteins are just a fraction of sales in the overall market, they are still worthy of attention.

Plant-based alternatives showed triple-digit growth early but slowed down significantly and has seen double-digit declines over the last year. The declines caused retailers to reevaluate merchandising decisions and move these items outside of the meat department, or just offer less SKUs overall.

“I do not believe, however, that the plant-based meat alternative trend has played out altogether,” Roerink said. “We are still too early in the innovation cycle to call it. We will continue to see new items become available with superior taste, texture and smell and as long as consumers are willing to continue to try them, I think we will continue to see ebbs and flows into the plant-based meat alternative market.”

Hixon said Midan’s research echoed Roerink’s sentiment.

“In research Midan did in 2021, almost half of meat consumers had a positive initial reaction when they heard the term ‘plant-based meat alternatives,’” he said. “However, in our 2021 research, only one in five surveyed meat consumers said they consume plant-based meat alternatives once a month or more. In the last year, we have seen a dramatic downfall in the number of plant-based units in the meat case.”

Cultivated meat, still not widely available, remains a question mark in terms of its future in the market. While some consumers believe it is a viable option, many don’t trust it for various reasons.

“Cultivated meat is an interesting area,” Roerink said. “People who have some concerns over the idea of eating meat and poultry from a health, animal, or planet point of view, like the idea of taking cells from the animal and growing it in a laboratory. However, the vast majority of Americans have some concerns relative to eating cultivated meat. A lot of these concerns center on food safety, taste, texture etc.”

According to Midan’s research, consumers have yet to make strong decisions on cultivated meat. As volume increases and pricing becomes more acceptable to consumers, Midan believes adoption of cultivated meat will exceed what has been seen for plant based.

“It will take time, but traditional animal protein production needs to be thinking about how to position their products to keep majority market share,” Hixon said.

Looking ahead

For the future processors need to pay close attention to inflation and how consumers react to it regarding their purchasing habits. Creating value for shoppers will help counter the spikes in prices, but processors must also understand value means different things to different demographics.

“For some, ‘value’ means the absolute lowest cost for highest number of meals – these consumers are buying more grinds and value cuts like roasts,” Hixon said. “For others, value-added products provide new flavors and save time. Others are choosing to save their dollars by recreating restaurant meals at home, and this opens a door for premium meats.”

According to the Power of Meat, year-on-year the price of groceries increased 15% and compared to pre-pandemic levels prices are up 25-27%, reinforcing inflation and the need for industry to respond. That on top of other financial pressures will affect shopper decision making.

“They are looking for more sale specials during a time when industry is having a hard time providing specials,” Roerink said. “People are looking for smaller packages, people are looking for proteins that are a little cheaper on the price per pound basis etc. So, figuring out how to continue to keep people in the category while not eroding the purchases of others will be an important conundrum to consider.”

She added that the meat purchasers themselves will change as time goes on, and companies need to adjust by paying attention to who is spending.

“If we look at the distribution of the food dollar in today’s market, we see that boomers and Gen X are the majority spenders. But if we look at growth, we see that millennials and Gen X are the ones who are driving a lot of the new dollars. So, we need to make sure that in our merchandising we address today’s shopper, but also start engaging tomorrow’s shopper.”

You might also enjoy:

Overcoming obstacles and chasing innovation, the pet food industry prepares for its promising future.

Looking ahead, producers, processors and retailers must appeal to evolving demographics.