By Michelle Smith

August 2022

A look

ahead

Technology that promotes sustainability, efficiency and connectedness will take the baking industry into the future.

Aspire Bakeries

The bakery of the future will be about making connections. It will, of course, boast the latest technology, helping companies enhance efficiency, protect the planet and improve conditions for workers. But it’s also about the connections made between factions inside the bakery and to the outside world, including suppliers, customers and consumers, creating greater transparency and understanding.

“For the bakery of the future, there are basically four areas of focus. First is trying to get even better around improving safety and conditions for associates, with unwavering focus on food quality and safety,” said Brett Buatti, chief supply chain and operations officer, Aspire Bakeries, Los Angeles. “It’s also about a focus on sustainability and about improving efficiency and costs. And finally, there is this notion of connectedness, which helps with all these priorities as well as engagement with your people. Sensor technology and the Internet of Things enable the ability to connect within a bakery, to see more, to be aware of more, and to stay highly engaged with your associates. And it also allows you to actually connect the inside of the bakery to the outside world, whether that be suppliers, equipment manufacturers and service people, customers or even consumers.”

Promising technology is not only on the horizon but is already part of bakeries now, although much of it is complex and systems are still being perfected.

It’s not easy being green

Large companies are setting ambitious goals to reduce their carbon footprints through reduced packaging waste, energy and water.

“Bakers always strive to be more efficient across the board to make the best use of the resources they have. Energy and energy costs are always top of mind, in particular today with the many global uncertainties that are at hand,” said Rasma Zvaners, vice president, regulatory and technical service, American Bakers Association. “The baking industry already has a tremendous track record for making facilities more energy efficient. Most bakers have assessed their facilities’ efficiencies and Scope 1 emissions (greenhouse gas emissions at their facilities). Now they are looking directly at Scope 2 opportunities — indirect emissions associated with the purchase of electricity, steam, heat or cooling.”

Grupo Bimbo SAB de CV, Mexico City, announced new sustainability goals in a May conference call that included becoming a net zero carbon emissions company by 2050, obtaining 100% of key ingredients through crop cultivation using regenerative agriculture practices by 2050, and ensuring that 100% of its packaging supports a circular economy by 2030. That comes on top of goals the company has already set, including using 100% renewable energy by 2025.

“We are in a decade of action, and this means we need to increase our speed to reach our sustainability goals,” Daniel J. Servitje, chairman and chief executive officer of Grupo Bimbo, said during the call. “In many areas, such as climate change and water management, [if] the world does not act more boldly, it may be too late. We want to be a part of this acceleration, and that is how I can sum up everything that nourishing a better world is. It means nourishing the well-being of people and nature at the same time because we can only make things better if we do both. It is about the planet and about the people that live on it.”

Earlier this year, Hostess Brands Inc., Lenexa, Kan., announced it would invest $120 million to $140 million to transform an idled bakery plant in Arkadelphia, Ark., into a state-of-the-art facility. The bakery will become the company’s most efficient and flexible operation and is expected to increase capacity for Donettes and other products by 20%, said Kevin Sandefur, vice president, operations strategy.

“We are building this bakery with a sustainability-first approach, and we are committed to making it the greenest Hostess bakery we have,” he said. “We’ve outlined our sustainability goals for our company in the Hostess Corporate Responsibility Report that we issued in May, and we expect our Arkadelphia bakery to lead the way in achieving those goals.”

The company is working to make its other bakeries more sustainable and efficient, Mr. Sandefur said, through the reduction of water, energy usage, packaging waste and other waste.

“At Hostess, we will focus on sustainability at our bakeries as we look forward,” he added. “From development to execution, we will approach manufacturing expansion in a sustainable way.”

Barry Edwards, vice president, corporate responsibility and sustainability, Aspire Bakeries, said that bakeries should follow LEED green energy standards when building and adopting standards that move them toward lower net carbon emissions. He also stressed the importance of building in the right place.

“Logistics are forever,” Mr. Edwards said. “There are a lot of miles involved in transporting any product, and the more you can think about where you can locate your facility to try and minimize the miles, whether incoming with raw materials or outgoing to the customer, the better off you’ll be. It makes sense to look at that and try to minimize as much as you can. It’s a long-term amount of miles that you’re going to be creating.”

Employing connected systems that provide real-time access to data will help facilities better manage resources and find problems right away, Mr. Buatti said, rather than seeing a spike in usage a week or month later when it’s too late to act on it.

“You can use the data in a lot of ways, including efficiency and quality,” he said. “It’s a natural extension to use it on sustainability-focused activities, too. So you can catch energy usage while it’s happening, you can catch wastewater discharge while it’s happening, and you can catch water usage while it’s happening.”

It’s clear bakeries understand that sustainability is an important part of future operations.

“Anything that reduces your overall impact to the environment, whether emissions or energy usage or waste, those are must-haves in the future,” Mr. Buatti said.

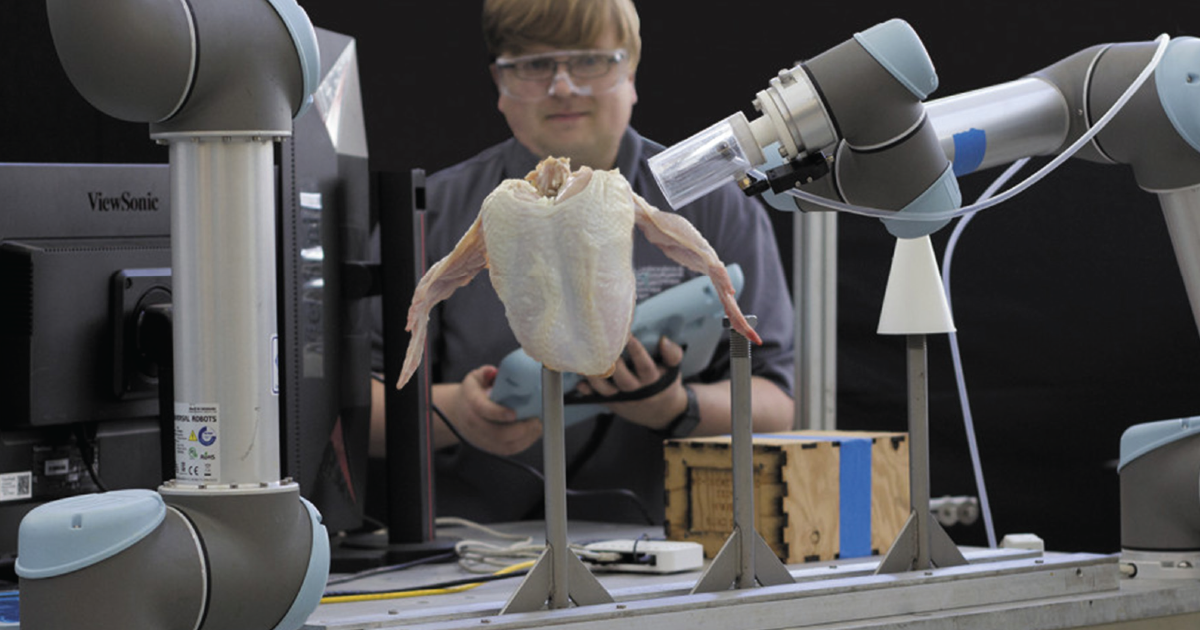

Automation and engagement

The bakeries of the future will have more advanced tools in the forms of robotics, data-capturing equipment, artificial intelligence (AI) and other technologies. This will involve high-speed internet and the use of the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) to connect bakeries to the outside world.

Bakeries large and small are turning to more complex and sophisticated forms of automation with a tight labor market and the need to run as fast and efficiently as possible.

“There’s old-school automation, which is sensors and motors, and there’s more advanced systems like robotics,” Mr. Buatti said. “Classic automation can be a bit limited in that it usually ends up doing a lot of the same thing very fast. However, that can really limit flexibility and can limit your product range or ability to innovate. You’ve got to balance the trade-off between efficiency and flexibility. What helps is when robotics advance enough to be flexible at really high speeds. There are applications in the present, but that’s when it becomes futuristic. How can we do all kinds of things but do it really fast?”

He stressed that it’s not about eliminating jobs in the bakery but making them more engaging. For instance, instead of an employee packaging items by hand, that person could be trained to oversee packaging machinery and robots. This improves skills and reduces repetitive motion injuries.

Real-time connectivity will help bakeries keep in close contact with suppliers and customers.

“That technology is out there; it’s just not fully perfected and realized within the four walls of the bakery,” Mr. Buatti said. “I can pull up on my screen right now what’s happening in the factories. What lines are running, what lines are down, how well they’ve run today. The notion of allowing customers access to something, even as simple as, ‘Yes, your product is running and here’s how much we’ve made,’ is very doable. But it’s a big question as to whether you’d want to or how you’d do it and what you’d share.”

He also sees better connectedness within the bakery benefitting the company and employees.

“If you get the right programmer, set it up the right way, you can have people see a piece of data, tag it and send it to someone who has another device in the bakery, saying, ‘Hey, I think you might be sending me product from upfront that’s too dry. You’ve got to adjust your moisture levels,’ ” he said. “Or they can say, ‘This is making a weird noise. Let me use my wireless device to turn on the camera that can show the mechanic who’s on the other side of the bakery what’s going on here.’ ”

These tools could link teams together and improve engagement by not just educating about problems to watch for but also celebrating successes with other team members. Mr. Edwards said these connections can make jobs more meaningful.

“People want to be a part of something bigger,” he said. “And in the long run, it helps the business because they’re noticing things that might not be right that they can get fixed in the process.”

Data collection and AI

Companies are using systems to tie in data from multiple production lines at multiple sites across the globe to help improve processes, said Jon Gilchrist, engineering manager at Sightline Process Control Inc., a KPM Analytics brand, which among other things provides vision systems for bakeries.

“We’ve seen deployments of these data systems where across the globe specific lines are being pulled into one data structure that’s presented for both decision-making and analysis purposes as well as just monitoring,” he said. “So being able to extract things like counts and common production issues from the data are a critical part of it.”

Collecting and analyzing data are enabling companies to make better decisions and identify causes of inconsistences that they otherwise would not have been able to identify, Mr. Gilchrist said.

“The real benefit is in that data, analyzing that and being able to identify where things are going wrong and solve those to actually reduce waste and increase your output,” he said. “That’s the critical side of it.”

The benefit of AI is to help bakeries break down copious complex data and make it useful, said Liran Akavia, co-founder and chief operating officer of Seebo, now part of Augury.

“Waste and quality are the two main challenges we see in particular that baked goods manufacturers want to address most urgently — and it’s here we see artificial intelligence providing major value,” he said. “These losses can take many forms: from overweight to size and shape inconsistencies, color variances, packaging errors and more. But the common thread is these losses are always due to inefficiencies within the production process itself, as opposed to asset-related issues, for example.”

Using AI in a bakery begins with defining business objectives, Mr. Akavia said. It’s the most critical phase because it allows all parties to focus on a concrete, measurable business goal, which is key to seeing the value of AI.

“I should emphasize that you don’t need to extract all possible data,” he said. “In fact, one important part of the adoption process is that our team guides the manufacturing team to extract precisely the data they need, which makes the time to benefit far quicker.”

Once implemented, the company’s algorithms learn the process and begin providing insights.

“Process experts gain the insights into why losses are happening and how to prevent them, and operators receive real-time alerts on when and how to act to prevent process inefficiencies and losses before they occur,” Mr. Akavia said.

As bakeries delve further into collecting data and sharing information, cybersecurity will be paramount.

“These sites have a duty to their own company and to their clients to maintain data security,” Mr. Gilchrist said. “That often means working with established processes or establishing new processes to deal with some of the changing requirements that come with integrating such a large data pool. … We’re seeing that enhanced push to get these pieces of equipment on the network, have access to them both from external and internal resources, and that definitely takes a lot of careful planning and consideration.”

He suggested that bakeries concerned about security partner with their suppliers as they have likely helped others with similar issues.

“The more we can align as an industry on solutions and adopt shared practices, I think that’s the best path forward and makes life easier for everybody,” Mr. Gilchrist said.

As companies set ambitious goals for sustainability, increased output and efficiency, they have many tools to help them improve their companies while helping employees and the planet. They just need to decide what they want their bakery of the future to look like.

You might also enjoy:

Overcoming obstacles and chasing innovation, the pet food industry prepares for its promising future.

Today’s meat and poultry processors carefully manage expectations to feed people, preserve the planet and deliver profits in the future.

Slaughtering and processing facilities where meat and poultry are manufactured have improved dramatically over the past 100-plus years.