By Laurie Gorton

May/June 2022

the bake

story

This innovative publishing platform now observantly reports about the changing face of retail baking.

It’s simple: wholesalers deal with customers, retailers deal with consumers. Communication style, too, shifts when serving retail bakery readers vs. wholesalers. That’s what makes bake so different from other Sosland Publishing brands.

Since its founding in 1987, the magazine has evolved steadily with the times. Originally titled Baking Buyer, it is now known as bake.

“The changes were made to make the content more engaging to our audiences,” says John Unrein, editor, bake and Supermarket Perimeter. “Baking Buyer became bake to reflect a more modern approach to the artistry and business aspects of retail baking.”

Mission oriented

Like most business-to-business publications, bake’s mission is both educational and advisory. It is aimed at educating the retail/specialty bakery audience about influential consumer purchasing and consumption trends affecting the current and future profitability of the fresh bakery industry, as well as to spotlight leading trends in the areas of ingredients, equipment, packaging, technology and business management. The magazine reaches retail bakery, artisan/specialty bakery, foodservice/bakery cafe and intermediate wholesaler audiences.

“bake magazine and bakemag.com are the quintessential resources — both online and in print — for all things baking in the retail bakery and bakery foodservice segments of the North American baking industry,” Unrein says.

Made to measure

bake is certainly the Sosland brand that has seen the most transformation in concept, content and format, thus reflecting the dynamic food retailing marketplace. Its mission today is far different, both more mature and more innovative, than the one that launched it in 1987.

The magazine started as a project of Sosland’s Baking Equipment (now known as Baking & Snack) because competitive pressure forced a demonstration of the ability of Sosland’s bakery audience to respond to advertising. It was a gambit in the numbers game of reader inquiries.

In pre-internet times, publishers urged readers to respond to ads and editorial items by filling out reader service cards, a.k.a. “bingo cards.” Introduced in the early 1960s, these cards could be found in most trade magazines a decade later. The postcards, bound into the magazine, carried a grid of numbers linked to ads and supplier new product news items.

The greater the number of inquiries a magazine generated, the more favorably it was viewed by many advertisers. Ad agencies, in particular, liked such response data because they made it easier to justify ad “buys” during an era that emphasized cost-per-thousand circulation analytics.

Sosland Publishing’s problem was that its bakery publications, Milling & Baking News and Baking Equipment, had far fewer recipients (by just more than half) than Bakery Production & Marketing (Gorman Publishing), the leading competitor. Baking Buyer supplemented its circulation to approach that of the competition.

Magazines that specialized in new product news were fairly common in the 1970s and 1980s. Usually published in tabloid size (11 by 17 in.), their business purpose was to generate sales leads. They circulated free of charge to qualified recipients, often the same list used by another of that publisher’s roster.

Baking Buyer covered product news from vendors and suppliers and was targeted at retail and intermediate wholesale bakers — the prime users of the Baking Equipment reader service card program. Mike Gude, publisher of Baking Equipment, headed up Baking Buyer sales, and Laurie Gorton, then editor of Baking Equipment, supervised the new magazine’s editorial content. The company worked with a University of Kansas journalism student to write the news items on a freelance basis.

“Those early issues look downright primitive when compared with the sophisticated approach, design and reader audience of today’s bake magazine,” Gorton says.

As the 21st century approached, the World Wide Web made reader service cards obsolete. The internet provides myriad opportunities for measuring reader traffic, page views and content interactions with highly precise analytics. Almost as soon as publishers launched their websites and digital editions, they mothballed their bingo cards.

The metamorphosis of reader service numbers into webpage addresses was not the only alteration made by Baking Buyer. Over the years, its content was enriched with feature articles. Its size also changed. The tabloid was modified in 2001 to standard size (8½ by 10½ in.), where it now remains.

In 2005, Baking Buyer split into two publications. “It was then that we increased our efforts to focus more specifically on the retail/specialty bakery segment with Baking Buyer and the in-store bakery with a separate publication, inStore Buyer, which became inStore in 2013,” says Troy Ashby, publisher, bake and Supermarket Perimeter.

Baking Buyer became bake in 2012.

The emerging importance of fresh foods, sold in departments set around the perimeter of supermarkets, led Sosland Publishing to enlarge the editorial coverage and reader audience of inStore, transitioning it into Supermarket Perimeter in 2019.

Circulation by business class finds 62% retail baking; 19% bakery cafe; 12% specialty baking; 5% food service distributor, bakery distributor and broker; and 2% intermediate wholesale bakery.

“There are more specific types of readers in our audience than other publications at Sosland,” Unrein says.

The magazine’s readership skews young, reflecting generational change within the industry and the entrance of many new bakers, especially those in their 20s and 30s. Cover photos often portray these trends and the people responsible. bake’s 2022 Media Guide reported US Census data stating that the retail baking segment employs nearly 200,000 workers, 64% of whom are female.

A dynamic field

The bake marketplace is widely diverse … and rapidly changing. “The retail industry continues to evolve, sometimes dramatically,” Unrein says. “When I started here, there were mostly family-owned retail shops and supermarket bakeries that both followed the same goals.

“Then specialization took hold of the industries,” he continues. “Retailers branched into cake shops, cookie specialists, pastry shops, donut stores and other retail shops that specialized in much more defined — and marketable — product lines. And supermarkets emerged as the leading competitors to retailers because of shifts in consumer buying patterns, such as more one-stop shopping.”

New product news, once the mainstay of Baking Buyer, has long since been superseded by feature content involving ingredients, formulas and technology, plus workplace management, financial controls, food safety, merchandising and shop design, as well as in-person operator profiles.

“New product introductions are certainly still important to our audience,” Ashby says. “As our print publications evolved and digital offerings expanded, new product spotlights have taken more of a digital-first direction. This is reflected by the fact that in nearly every digital newsletter we deliver to our audiences, there is a new product spotlight section of the newsletter — some being sponsored sections, others driven by our editorial teams.”

You might also enjoy:

Business intelligence and market analysis address the needs of readers throughout the food processing industry.

Sosland Publishing’s new publication offers insight into a dynamic industry.

Monthly magazine explores how, where and why supermarket innovations happen.

Industry trends

“Our story is your story. During tough times and those filled with prosperity, the retail baking industry has advanced through the determination of family businesses dedicated to knowledge of their craft and solid work ethic,” Unrein wrote in his Editor’s Note column in the May/June 2021 issue of bake about coming articles celebrating the Sosland Centennial. To date, these reports have been published in 2021 issues of May/June, July/August and September/October and the 2022 issue of March/April.

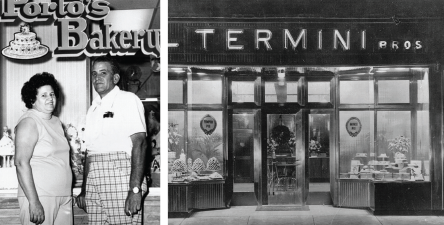

A little more than a century ago, retail bakers organized a professional association, the Retail Bakers of America. Its first annual meeting was scheduled for October 1918 but was postponed because of the influenza pandemic then raging.

For most of the 20th century, retail baking was dominated by family businesses, usually founded by an immigrant masterbaker and serving primarily local markets. On a national scale, supermarkets entered retail baking with small in-store shops, made possible by the advent of frozen doughs and flexible small-scale commercial mixing, proofing and baking equipment introduced in the 1970s.

By the 1990s, the artisan bread movement had started to revamp retail baking’s product lines and ownership profiles. It was centered at first on the West Coast but rapidly spread throughout the country. This new/old bakery style attracted a new group of bakery operators, often young people from outside the traditional baking professions. The celebrity baker emerged side by side with the celebrity chef. The Bread Bakers Guild, the champion of artisan baking, formed in 1993. The James Beard Award, created in 1990 and now considered the food industry’s highest honor, has recognized Outstanding Pastry Chef from its start and, more recently, Outstanding Baker among its award categories.

Today, US retail bakers rival any in the world in their expertise, evidenced by 2005’s victory at the world’s most prestigious event for craft bakers, the Coupe du Monde de la Boulangerie (World Cup of Baking) held in Paris — the second time in three occasions that Americans achieved this distinction.

Specialty flours, particularly organic styles, rose in attention and usage by the retail baking segment. Whole grain, gluten-free, non-GMO and vegan, plus fiber enrichment, have found a place on the retail baker’s menu boards. The late 1990s finally saw a licensing solution to the legal problems that previously occurred when bakers depicted popular characters from movies and comics on decorated cakes.

Technology has improved, too, as computer-aided processing equipment became available in this market, thus leveraging the masterbaker’s knowledge and skills over a wider range of employee capabilities. But the big change in retail baking has been the rising use of the internet and social media. Not only do bakers find it easier to advertise and describe their products in this fashion, but it has also fostered creation of unique products. Think cronut, or duffin, or cake truffle. Or even a wedding cake non-fungible token (NFT).

American retail bakers have now caught up with the bakery cafe format so popular in Europe, and retail bakeries also figure in the pop-up trend, the newest form of food retailing.

Radical redesign

Over the years, Baking Buyer evolved from a product tabloid into a full-fledged business magazine. But in 2001, its readers found something entirely new in their mailboxes. The magazine mounted a total redesign. Everything changed. The impact was immediate.

“Who said that business-to-business books had to look like trade magazines anyway?” opined then-editor Kerri Conan, in the January 2001 issue as she introduced readers to the new look.

Prefacing this effort was a plan drawn up by the publisher and editors for a comprehensive overhaul of content. The magazine’s design team knew the editorial shift was intended to better serve the retail marketplace and its readers’ focus on consumer as well as business needs. That led them to evaluate contemporary mass media, rather than review just business-to-business titles. They deliberately pursued the “look and feel” of popular lifestyle magazines. Additional white space. More photos. More graphics. More art. Text, set in ultra-fashionable fonts, was leaded a few points extra to let in more “air.” Color blocks in graded shades and tints replaced red, blue and other bright colors previously in use.

Restyling went more than skin deep. Content changed, too. News coverage turned into departments, each named for a targeted subject area. Feature stories spread out over several pages, made easier to read and were compartmentalized with sidebars, charts and “sound bites.”

“The goal is to create a magazine with more entry points so that the information you care about pops up fast,” Conan wrote. “The hope is that you linger and discover items you may not have realized could impact your business.”

She described the “new” magazine as providing “insight for business on the rise.”

Unrein joined the magazine’s staff in March that year, taking over as editor. Looking back, he said, “The redesign dramatically increased the value and readership of Baking Buyer, now bake.”

The new look did not go unnoticed by the magazine’s publishing peers. The very next year, Baking Buyer received national recognition, named as a top-three finalist in Folio magazine’s annual Ozzie Awards for best overall magazine redesign. The magazine’s designer, Cayce Richardson, accepted the award.