By Jeff Gelski

July 20, 2021

A Century of

Frozen Food Progress

Canadian fishermen, microwaves and cauliflower move the category forward

Frozen food has appealed to changing consumer desires for more than a century, from quality and convenience to health and gluten-free concerns. Breakthrough ideas have come from unexpected sources, including fishermen in Canada, turkeys in railroad cars and children with celiac disease.

Freezing fish inspiration

The quality of frozen food was lacking before Clarence Birdseye headed north. Freezing food early in the 20th century required large blocks of ice. The slow process led to ice crystals embedded in the food, resulting in poor taste and quality, said Dan Skinner, communications manager at Chicago-based Conagra Brands, Inc., which now owns the Birds Eye brand.

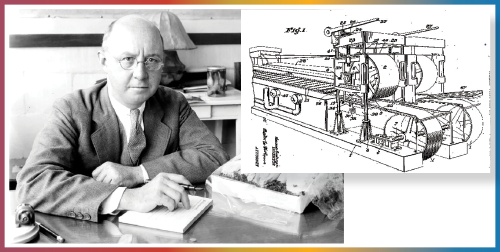

Mr. Birdseye’s link to frozen food began when he was working with the US Department of Interior in Labrador, an area in northeast Canada, in the 1920s. When the Inuit fished there, Mr. Birdseye noticed how they used ice, wind and temperature to instantly freeze fish.

Upon returning to the United States, he worked on replicating this flash-freezing process. His invention consisted of two metal belts chilled to negative 45° Fahrenheit. Food, including fish, meat and vegetables, could be pressed between the two belts and frozen quickly, Mr. Skinner said.

Mr. Birdseye received a patent for his flash-freezing process in 1927 and then sold it to Goldman Sachs, where he stayed on as a consultant, Mr. Skinner said. The first Birds Eye products entered the market in 1930.

“There was a little initial skepticism, but once people realized this was a quality product, it quickly took off,” Mr. Skinner said.

General Foods, Dean Foods and Pinnacle Foods all owned the Birds Eye brand at different times throughout the years until Conagra Brands acquired Pinnacle Foods in 2019.

Too many turkeys

Decades after the debut of the Birds Eye brand, Swanson Foods encountered a problem: What to do with 260 tons of frozen turkeys sitting in railroad cars.

“In 1953 Swanson had made a bad read on the number of Thanksgiving turkeys they were going to need,” Mr. Skinner said.

The miscalculation led to Swanson creating its TV dinner. Who should receive credit for it remains the subject of debate. Some point to Gerry Thomas, a salesman who suggested Swanson combine the excess turkey with cornbread dressing and vegetables on the assembly line, creating a frozen dinner, Mr. Skinner said. Brothers Gilbert and Clarke Swanson, leaders of the company, led the TV dinner project as well. Betty Cronin, a bacteriologist working for Swanson Foods, figured out how much time would be needed to cook three different food items.

“It was much more of a team project than any one person,” Mr. Skinner said.

Thanks to the TV dinner, Americans could eat while watching “I Love Lucy.” Swanson sold 10 million turkey dinners in 1954.

The microwave marriage

The history of the Stouffer’s brand, a rival to Swanson, dates to 1922 when the Stouffer family opened a restaurant in Cleveland, according to Nestle SA, Vevey, Switzerland, which now owns the brand. The family went on to open a chain of restaurants. Freezing items allowed the company to sell them to consumers as take-home items. By 1954 Stouffer’s restaurants were serving over 14 million meals, and the company was creating frozen entrees, too.

Stouffer’s gained an edge over Swanson in one area: speed. Litton Industries, Inc., which offered brand-name products like Litton microwave ovens, acquired Stouffer Foods Corp. in 1967, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. The microwave oven became a way to heat frozen foods more quickly.

Nestle acquired the Stouffer’s brand in 1973. Lean Cuisine entrees, each containing fewer than 300 calories, were introduced in 1981.

Cauliflower crust

Earlier this century Gail Becker knew how to heat and eat frozen food, but that was about it.

“If it’s possible to know less than nothing, then that is what I knew,” she said.

Since her two sons with celiac disease could not eat gluten, she began experimenting in her kitchen, making gluten-free pizza with cauliflower crust. The trial-and-error efforts eventually led to a satisfying product, and the creation of Caulipower, a frozen pizza brand.

Early on, Ms. Becker read about the frozen food industry and spoke to as many people as she could, learning new words and what certain acronyms meant.

“And I hired a lot of people much smarter than me to teach me about the business, and I was like a sponge quite frankly,” she said. “I learned something new every day. I’m still learning something new every day.”

Once the Caulipower frozen pizza caught on, it brought new consumers into the frozen foods aisle.

“I think that’s one of the reasons why retailers are very much drawn to the brand,” Ms. Becker said.

Recent resurgence

Ms. Becker sold the first Caulipower pizza in February 2017. That same month Packaged Facts, Rockville, Md., released a report stating overall US sales in the frozen food category were flat. Packaged Facts projected US sales would fall to $21 billion in 2021 from $22 billion in 2016 in the four frozen foods categories of frozen dinners/entrees, frozen pizzas, frozen side dishes and frozen appetizers/snacks. Product innovation, including bold flavors, varieties inspired by world cuisines and products with healthier nutritional profiles, were strengthening the market, according to the report.

Sales picked up after the report came out. Then they soared during COVID-19 as more consumers ate at home.

Packaged Facts, in a June 2020 report, revealed US frozen pizza sales registered a compound annual growth rate of 2.6% from 2014-19, rising to $5.63 billion in 2019 from $4.94 billion in 2014. Packaged Facts projected sales to hit $6.38 billion in 2020, drop to $5.97 billion in 2021 and eventually reach $6.49 billion in 2024 thanks to a forecast 2.9% CAGR from 2019-24.

US frozen food sales grew 23% in the first half of 2020 when compared to the first half of 2019, according to Acosta, Inc., Jacksonville, Fla., an integrated sales and marketing provider in the consumer packaged goods industry. In the second half of 2020, the sales growth was 18%.

“As COVID-19 set in, consumers began eating at home more out of necessity,” said Colin Stewart, executive vice president, business intelligence at Acosta. “To adapt, they searched for new ways to cook creatively, and for many, frozen foods were the answer. Total frozen sales grew 20.6% from 2019 to 2020, outpacing the growth of total store and total edibles.

“Frozen foods have come a long way, and recent innovation has driven the appeal from mere convenience at the expense of taste and quality to something for every palate and dietary concern. The category’s expanded offerings give consumers a quick and cost-friendly way to enjoy diverse dishes in the safety of their own homes.”

Innovation has come in the historic Birds Eye brand, which now offers vegetable-based pasta and zucchini-based noodles, Mr. Skinner said.

“We’ve got a rice cauliflower offering that is really popular,” he said. “We have fried cauliflower offerings that are very popular in bars and restaurants right now.”

Nestle SA in 2021 is exploring ways to expand in plant-based items. Company sales in plant-based meat analogs are over $200 million, said Ulf Mark Schneider, chief executive officer, in a Feb. 18 earnings call.

“But when you look at the wider opportunity, when you look at where we use these ingredients to then make more attractive downstream offerings like frozen pizza with plant-based toppings or frozen meals or other prepared dishes, then it’s a much bigger opportunity,” he said.

Ms. Becker has kept the frozen food innovation coming at Caulipower. Besides pizza, the company in the frozen food category has expanded into cauliflower chicken tenders, pasta and rice.

What idea will next advance the frozen food industry? Ms. Becker said it could be home delivery.

“The cost of frozen shipping to end consumers is still very high,” she said. “I think that is something that is ripe for innovation.

You might also enjoy:

Retailers try to keep up with ever-changing definitions of health and wellness.

As the snack industry grows and changes, consumers are gobbling up a variety of treats.

A look at nearly a century of Nestlé Purina meeting the nutritional needs of pets as the industry has evolved.